I have a particular programming style regarding constructors in Java that often sparks curiosity and discussion. In this blog post, I want to note my part in these discussions down.

Let’s start with the simplest example possible: A class without anything. Let’s call it a thing:

public class Thing {

}There is not much you can do with this Thing. You can instantiate it and then call methods that are present for every Object in Java:

Thing mine = new Thing();

System.out.println(

mine.hashCode()

);This code tells us at least two things about the Thing class that aren’t immediately apparent:

- It inherits methods from the Object class; therefore, it extends Object.

- It has a constructor without any parameters, the “default constructor”.

If we were forced to write those two things in code, our class would look like this:

public class Thing extends Object {

public Thing() {

super();

}

}That’s a lot of noise for essentially no signal/information. But I adopted one rule from it:

Rule 1: Every production class has at least one constructor explicitly written in code.

For me, this is the textual anchor to navigate my code. Because it is the only constructor (so far), every instantiation of the class needs to call it. If I use “Callers” in my IDE on it, I see all clients that use the class by name.

Every IDE has a workaround to see the callers of the constructor(s) without pointing at some piece of code. If you are familiar with such a feature, you might use it in favor of writing explicit constructors. But every IDE works out of the box with the explicit constructor, and that’s what I chose.

There are some exceptions to Rule 1:

- Test classes aren’t instantiated directly, so they don’t benefit from a constructor. See also https://schneide.blog/2024/09/30/every-unit-test-is-a-stage-play-part-iii/ for a reasoning why my test classes don’t have explicit constructors.

- Record classes are syntactic sugar that don’t benefit from an explicit constructor that replaces the generated one. In fact, record classes use much of their appeal once you write constructors for them.

- Anonymous inner types are oftentimes used in one place exclusively. If I need to see all their clients by using the IDE, my code is in a very problematic state, and an explicit constructor won’t help.

One thing that Rule 1 doesn’t cover is the first line of each constructor:

Rule 2: The first line of each constructor contains either a super() or a this() call.

The no-parameters call to the constructor of the superclass is done regardless of my code, but I prefer to see it in code. This is a visual cue to check Rule 3 without much effort:

Rule 3: Each class has only one constructor calling super().

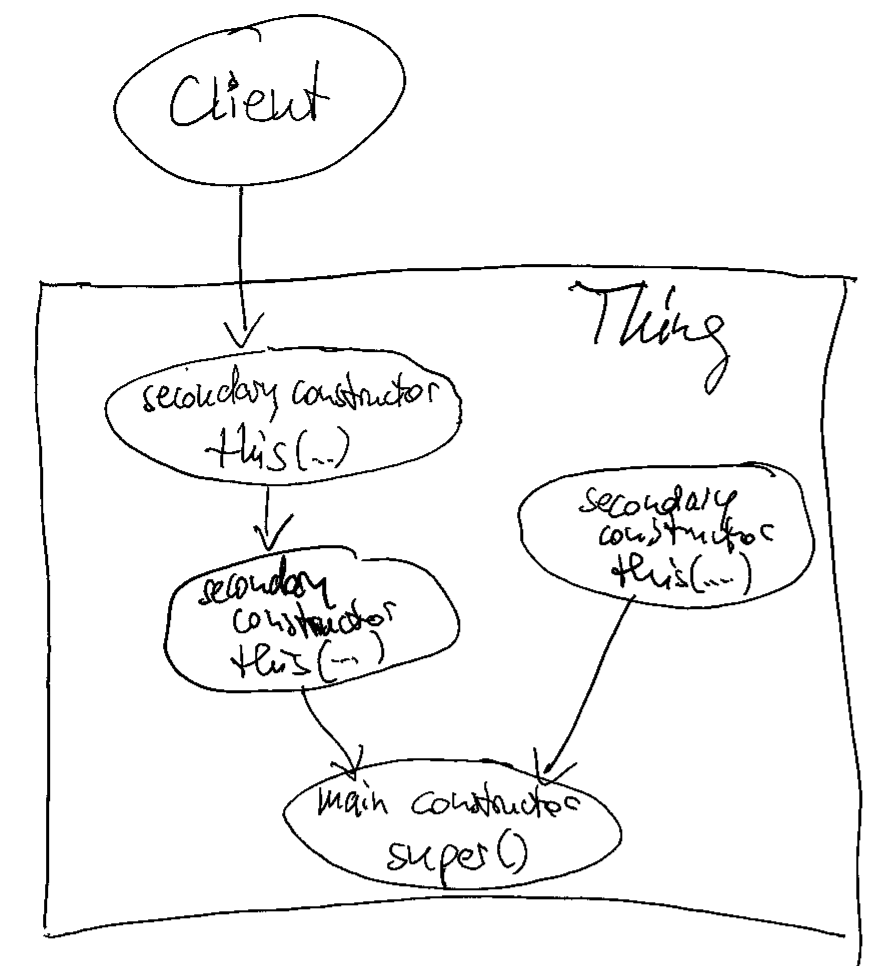

If you incorporate Rule 3 into your code, the instantiation process of your objects gets much cleaner and free from duplication. It means that if you only exhibit one constructor, it calls super() – with or without parameters. If you provide more than one constructor, they form a hierarchy: One constructor is the “main” or “core” constructor. It is the one that calls super(). All the other constructors are “secondary” or “intermediate” constructors. They use this() to call the main constructor or another secondary constructor that is an intermediate step towards the main constructor.

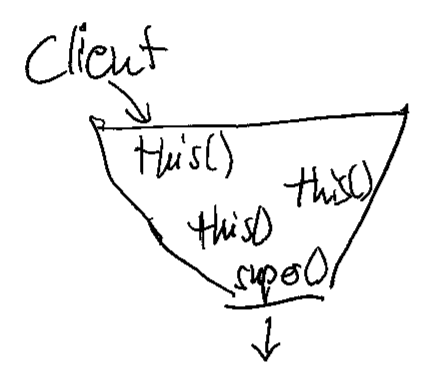

If you visualize this construct, it forms a funnel that directs all constructor calls into the main constructor. By listing its callers, you can see all clients of your class, even those that use secondary constructors. As soon as you have two super() calls in your class, you have two separate ways to construct objects from it. I came to find this possibility way more harmful than useful. There are usually better ways to solve the client’s problem with object instantiation than to introduce a major source of current or future duplication (and the divergent change code smell). If you are interested in some of them, leave a comment, and I will write a blog entry explaining some of them.

Back to the funnel:

if you don’t see the funnel yet, let me abstract the situation a bit more:

This is how it looks in source code:

public class Thing {

private final String name;

public Thing(int serialNumber) {

this(

"S/N " + serialNumber

);

}

public Thing(String name) {

super();

this.name = name;

}

}I find this structure very helpful to navigate complex object construction code. But I also have a heuristic that the number of secondary constructors (by visually counting the this() calls) is proportional to the amount of head scratching and resistance to change that the class will induce.

As always, there are exceptions to the rule:

- Some classes are just “more specific names” for the same concept. Custom exception types come to mind (see the code example below). It is ok to have several super() calls in these classes, as long as they are clearly free from additional complexity.

- Enum types cannot have the super() call in the main constructor. I don’t write a comment as a placeholder; I trust that enum types are low-complexity classes with only a few private constructors and no shenanigans.

This is an example of a multi-super-call class:

public class BadRequest extends IOException {

public BadRequest(String message, Throwable cause) {

super(message, cause);

}

public BadRequest(String message) {

super(message);

}

}It clearly does nothing more than represent a more specific IOException. There won’t be many reasons to change or even just look at this code.

I might implement a variation to my Rule 2 in the future, starting with Java 22: https://openjdk.org/jeps/447. I’m looking forward to incorporating the new possibilities into my habits!

As you’ve seen, my constructor code style tries to facilitate two things:

- Navigation in the project code, with anchor points for IDE functionality.

- Orientation in the class code with a standard structure for easier mental mapping.

It introduces boilerplate or cruft code, but only a low amount at specific places. This is the trade-off I’m willing to make.

What are your ideas about this? Leave us a comment!