Java enums were weird from their introduction in Java 5 in the year 2004. They are implemented by forcing the compiler to generate several methods based on the declaration of fields/constants in the enum class. For example, the static Enum::valueOf(String) method is only present after compilation.

But with the introduction of default methods in Java 8 (published 2014), things got a little bit weirder if you combine interfaces, default methods and enums.

Let’s look at an example:

public interface Person {

String name();

}Nothing exciting to see here, just a Person type that can be asked about its name. Let’s add a default implementation that makes clearly no sense at all:

public interface Person {

default String name() {

return UUID.randomUUID().toString();

}

}If you implement this interface in a class and don’t overwrite the name() method, you are the weird one:

public class ExternalEmployee implements Person {

public ExternalEmployee() {

super();

}

}We can make your weirdness visible by creating an ExternalEmployee and calling its name() method:

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

ExternalEmployee external = new ExternalEmployee();

System.out.println(external.name());

}

}This main method prints the “name” of your external employee on the console:

1460edf7-04c7-4f59-84dc-7f9b29371419Are you sure that you hired a human and not some robot?

But what if we are a small startup company with just a few regular employees that can be expressed by a java enum?

public enum Staff implements Person {

michael,

bob,

chris,

;

}You can probably predict what this little main method prints on the console:

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println(

Staff.michael.name()

);

}

}

But, to our surprise, the name() method got overwritten, without us doing or declaring to do so:

michaelWe ended up with the “default” generated name() method from the Java enum type. In this case, the code generated by the compiler takes precedence over the default implementation in the interface, which isn’t what we would expect at first glance.

To our grief, we can’t change this behaviour back to a state that we want by overwriting the name() method once more in our Staff class (maybe we want our employees to be named by long numbers!), because the generated name() method is declared final. From the source code of the enum class:

/**

* @return the name of this enum constant

*/

public final String name() {

return name;

}The only way out of this situation is to avoid the names of methods that are generated in an enum type. For the more obscure ordinal(), this might be feasible, but name() is prone for name conflicts (heh!).

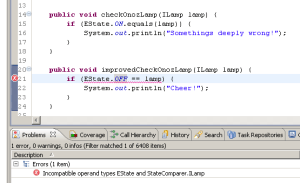

While I can change my example to getName() or something, other situations are more delicate, like this Kotlin issue documents: https://youtrack.jetbrains.com/issue/KT-14115/Enum-cant-implement-an-interface-with-method-name

And I’m really a fan of Java’s enum functionality, it has the power to be really useful in a lot of circumstances. But with great weirdness comes great confusion sometimes.