In this series about describing unit tests with the metaphor of a stage play that tells short stories about your system, we already published four parts:

Today, we look at the critics.

An integral part of the theater experience is the appraisal of the critics. A good review of a stage play can multiply the viewer count manyfold, while a bad review can make avid visitors hesitate or even omit the visit.

In our world of source code and unit tests, we can define the whole team of developers as critics. If they aren’t fond of the tests, they will neglect or even abandon them. Tests need to prove their worth in order to survive.

Let us think a little deeper about this aspect: Test code is evaluated more critically than any other source code! Normal production code can always claim to be wanted by the customer. No matter how bad the production code may look and feel like, it cannot just be deleted. Somebody would notice and complain.

Test code is not wanted by the customer. You can delete a test and it would not be noticed until a regression bug raises the question why the failing functionality wasn’t secured by a test. So in order to survive, test code needs a stakeholder inside the development team. Nobody outside the team cares about the test.

There is another difference between production code and test code: Production code is inherently silent during development. In contrast to this, test code is programmed to drive the developer’s attention to it in case of a crisis. It is code that tries to steal your focus and cries wolf. It is the messenger that delivers the bad news.

Test code is the code you’ll likely read in a state of irritation or annoyance.

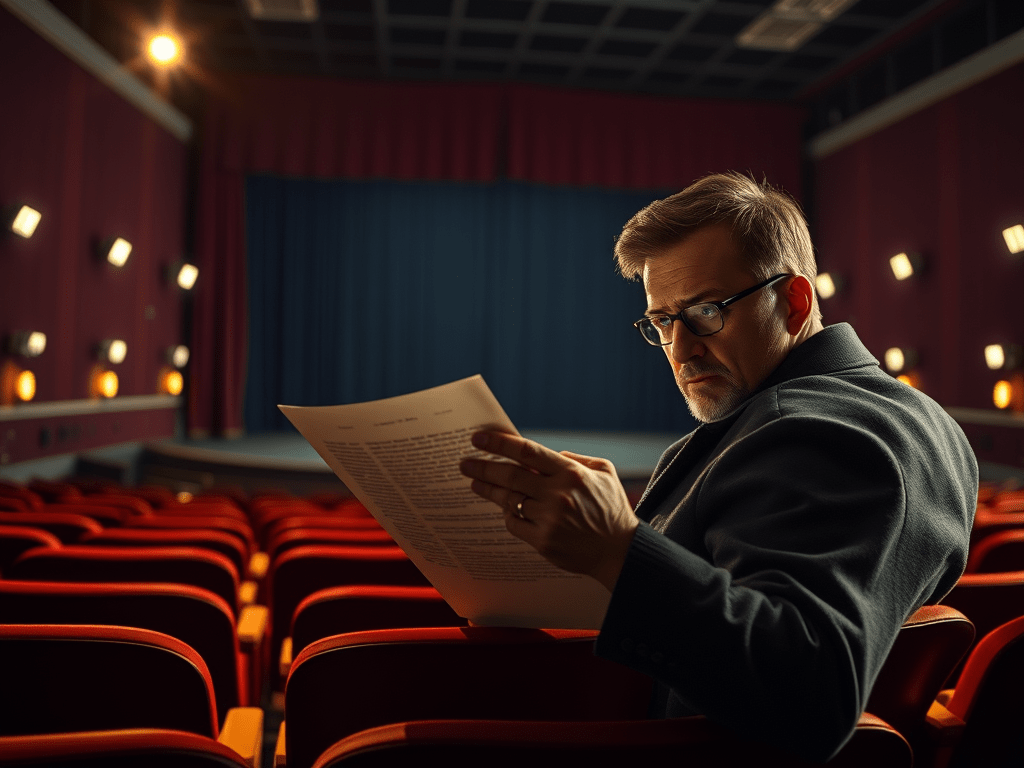

Think about a theater critic that visits and rates a stage play in a state of irritation and annoyance. That wanted to do something else instead and probably has a deadline to meet for that other thing. His opinion is probably biased towards a scathing critique.

We talked about several things that test code can do to be inviting, concise, comprehendible and plausible. What it can’t do is to be entertaining. Test code is inherently boring. Every test is a short story that seems trivial when seen in isolation. We can probably anticipate the critique about such a play: “it meant well, but was ultimately forgettable”.

What can we do to make test code more meaningful? To convey its impact and significance to the critics?

In the world of theater (and even more so: movies), one strategy is to add “big names” to the production: “From the director of Known Masterpiece” or “Part III of the Successful Series”.

Another strategy is to embellish oneself with other critiques (hopefully good ones): “Nominated for X awards” or “Praised by Grumpy Critic”.

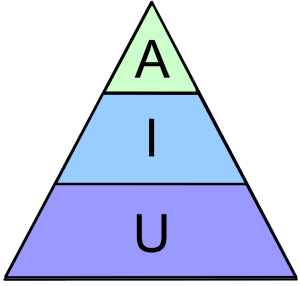

Let’s translate these two strategies into the world of unit tests:

Strategy 1: Borrow a stakeholder by linking to the requirement

I stated above that test code has no direct stakeholder. That’s correct for the code itself, but not for its motivation to exist. We don’t write unit tests just to have them. We write them because we want to assert that some functionality is present or some bug is absent. In both cases, we probably have a ticket that describes the required change in depth. We can add the “big name” of the ticket to the test by adding its number or a full url as a comment to the test:

/**

* #Requirement http://issuetracker/TICKET-3096

*/

@Test

public void understands_iso8601_timestamp() {

final LocalDateTime actual = SomeController.dateTimeFrom(

"2023-05-24T17:30:20"

);

assertThat(

actual

).isEqualTo(

"2023-05-24T17:30:20"

);

}The detail of interest is the comment above the test method. It explains the motivation behind authoring the test. The first word (#Requirement) indicates that this is a new feature that got commissioned by the customer. If it was a bugfix test instead, the first word would be #Bugfix. In both cases, we tell future developers that this test has a meaning in the context of the linked ticket. It isn’t some random test that annoys them, it is the guard for a specific use case of the system.

Strategy 2: Gather visible awards for previous achievements

Once you get used to the accompanying comment to a test method, you can see it as some kind of billboard that displays the merit of the test. Why not display the heroic deeds of the test, too? I’ve blogged about the idea a decade ago, so this is just a quick recap:

/**

* #Requirement http://issuetracker/TICKET-3096

* @lifesaver by dsl

* @regression by xyz

*/

@Test

public void understands_iso8601_timestamp() {

/* omitted test code */

}Every time a test does something positive for you, give it a medal! You can add it right below the ticket link and document for everybody to see that this test has earned its place in the code base. Of course, you can also document your frustrating encounters with a specific test in the same way. Over time, the bad tests will exhibit several negative awards, while your best tests will have several lifesaver medals (the highest distinction a test can achieve).

So, to wrap up this part of the metaphor: Pacify the inevitable critics of your test code by not only giving them pleasant code to look at but also context information about why this code exists and why they should listen to it if it happens to have grabbed their attention, even with bad news.

Epilogue

This is the fifth part of a series. All parts are linked below: