Since a few weeks ago, I am trying to find a few easy things to look for when facing a Merge Request (also called “Pull Request”) that is too large to be quickly accepted.

When facing a larger Merge Request, how can one rather quickly decide whether it is worth going through all changes in one session, or to decide that this is too dangerous and reject.

These thoughts apply for a medium-sized repository – I am of the opinion that if you happen to work in a large project, or contribute to a public open-source repository, one should never even aim for larger merge requests, i.e. they should be rejected if there is more than one reason any code changed in that MR.

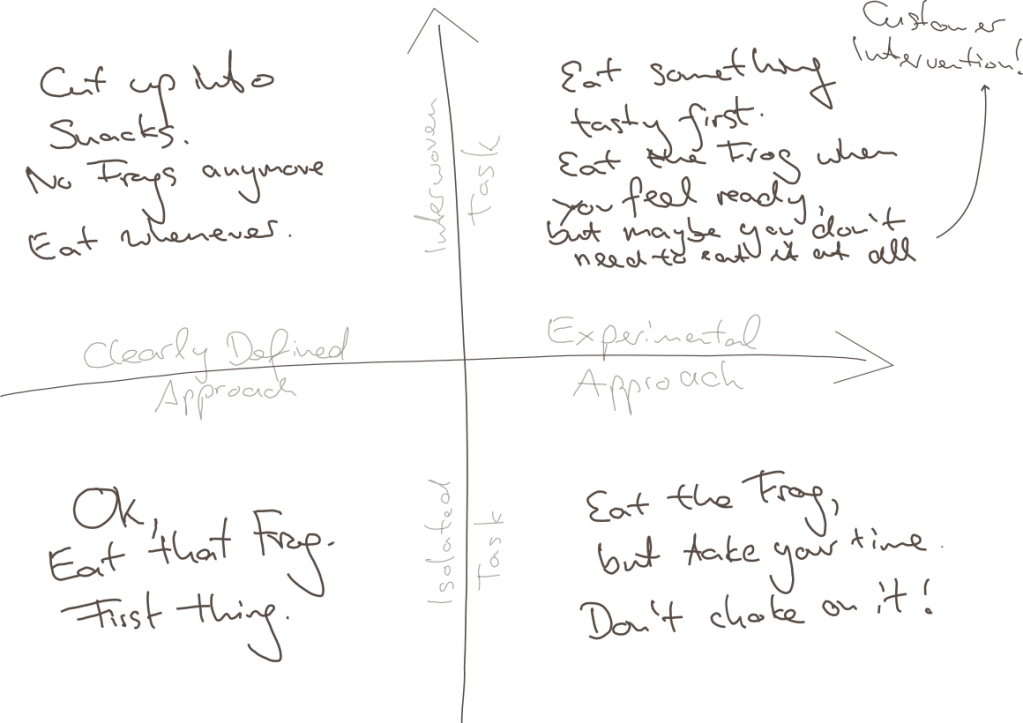

Being too strict just for the sake of it, in my eyes, can be a costly mistake – You waste your time in unnecessary structure and, in earlier / more experimental development stages, you might not want to take the drive out of a project. Nevertheless, maintainers need to know what’s going on.

Last time, I kept two main thoughts open, and I want to discuss these here, especially since they now had time to flourish a while in the tasty marinade that is my brain.

Can you describe the changes in one sentence?

I want my code to change for a multitude of reasons, but I want to know which kind of “glasses” I read these changes with. For me, it is a lesser problem to go through many changes if I can assign them to the same “why”. I.e. introducting i18n might change many lines of codes, but as these happen for the same reason, they can be understood easily.

But if, for some reason, people decide to change the formatting (replace tabs with spaces or such shenanigans), you better make sure that this the only reason any line changes. If there is any other thing someone did “as it just appeared easy” -reject the whole MR. That is no place for the “boy scout rule”, it is just too dangerous.

For me, it is too little to always apply the same type of glasses to any Merge Request there is. One could say “I only look for technical correctness”. But usually I can very well allow myself some flexibility there. I need to know, however, that all changes happened for only a few given reasons, because only then I can be sure that the developer did not actually loose track of his goal somewhere on the way.

Does this Merge increase the trust in a collaboration?

From a bird-eye point of view, people working together should always pay attention whether a given trajectory goes in the direction of increasing trust. Of course, if you fix a broken menu button in a user interface of a large project, the MR should just do that – but if you are in a smaller project with the intention of staying there, I suggest that every MR expresses exactly that: “I understand what is important at the current stage of this collaboration and do exactly that”.

Especially when working together for a longer time, it can be easy to let the branching discipline slip a little – things might have gone well for a longer time. But this is a fragile state, because if you then care too little about the boundaries of a specific MR, this can damage the trust all too easily.

In a customer project, this trust goes out to the customer. This might be the difference between “if something breaks they’ll write you a mail, you fix it, they are happy” and “they insist on a certain test coverage”.

Conclusion

So basically, reviewing the code of others boils down to writing own code, or improving User Experience, or managing anything – think not in a list of small-scale checklists, think in terms of “Cognitive Load”. A good programmer should have a large set of possible glasses (mindsets) through which they see code, especially foreign code. One should always be honest whether a given change is compatible with only a very small number of reasons. If there is a Merge Request that allows itself to do too much, this is not the Boy Scout Rule – it is a recipe of undermining mutual trust. Do not overestimate your own brain capacity. Reject the thing, and reserve that capacity for something useful.