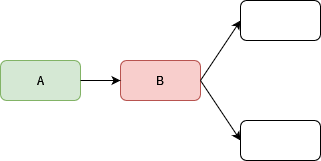

Some years ago, I had a software project that wanted to integrate a new kind of machinery into an existing application. Thanks to a modular and layered architecture, you could swap out the old machinery module and replace it with a new one. So it came down to writing an elaborate adapter between the existing application code and the new machinery interface. Shouldn’t be too hard, right?

And at first, it wasn’t. The machinery interface was relatively narrow, with just a few data registers to read from and write into. One core functionality of the old and the new machinery was moving equipment around at different axes (horizontally, vertically, etc.). The difference was: The old machinery was based on position switches, the new one operated on a sensor-based positioning system.

Position switches are rudimentary technology: An engine drives along the axis until it triggers the position switch that shuts of the engine. The advantage is a basic set of commands: Drive left (until you hit a switch) or drive right (until you hit a switch). This machinery control can be implemented by analog relais logic. The downside is that there is only guessing where the engine actually is at any moment if it doesn’t reveal its position by triggering a switch.

The new machinery works with a fancier method of positioning and movement. The control unit of the machine keeps track of the coordinates for every axis of movement. If you want the machine to assume a different position, you transmit the target coordinates and the machine moves until the difference is zero.

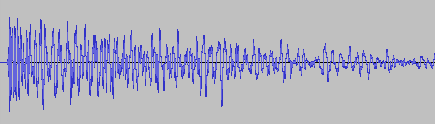

In reality, it wasn’t that easy. You also needed to transmit the desired velocity of the movement. The target was reached once the coordinates were equal to the transmitted coordinates and the actual velocity of all axes was zero again.

Okay, so making the new machinery move was a two-step transmission: First, you give it the target coordinates, then the speed values. And then you wait until things are like you want them to be.

The new module worked flawlessly with the new machinery. We could move it around in the boring one-dimensional ways the actual use case required or we could make it dance in complicated courses. The customer was pleased and the machinery was installed to perform the one-dimensional movements from now on.

The project was finished successfully. But after a while, the customer had a complaint. Seldom, but reocurring, the machinery would not move when commanded to, but blow a fuse and go into an error state.

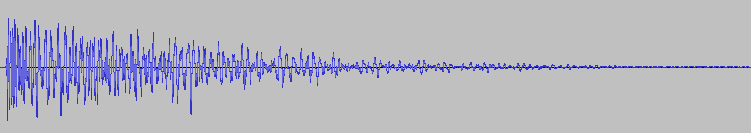

Initially, the customer treated it as an electrical problem within the machinery. Until the manufacturer couldn’t find a cause and suspected my software to transmit faulty command parameters. I implemented an exhaustive logging of all transmissions and could prove that the parameters were as correct as they were boring. The application transmitted “full left” or “full right” for the horizontal movement and nothing else.

We were all stumped and out of ideas until I had an idea out of the blue:

What if the command interface to the machinery has a hidden assumption that is not met by the application?

But why did it work 99 percent of the time? Wouldn’t the assumption be present for every movement command?

Every time I hear “spurious failure”, I think about a concurrency problem. But my module worked strictly serial, one command after the other. There was nothing going on concurrently on my side.

And then it dawned me: The concurrent process is the main loop of the machine control unit. The machine control unit essentially runs a single thread that performs a series of steps in an endless loop: Check machine status, check command registers, apply commands, do other machinery stuff, repeat.

What if the “check command registers” step occurs right when my software is in the middle of transmitting the target parameters? It would read a partially written set of parameters. More specifically it would read new target coordinates, but not the necessary velocities. It would calculate delta distances and try to move, but with absurdly low or high velocities, depending on the formulas. If at any point a division by velocity occurs, it would divide by zero.

Because I couldn’t review the code of the machine control unit and the original programmer of it wasn’t available anymore, I tested my hypothesis by reversing the parameter write order: velocity first, location last.

And I wasn’t wrong: This little change got rid of the spurious failures.

The hidden assumption of the control unit code was that all parameters were transactionally valid at any given time. This translated to an implicit protocol requirement: All clients of the command interface needed to either

- Transmit all changes at once (not possible with the technology that was used for transmission)

- Transmit the changes in an order that has no effect until all changes are written.

The second option was what I implemented. Instead of “steer, then accelerate”, I needed to “accelerate, then steer”, because velocity without a delta distance would not move the equipment, but delta distance without velocity would attempt to do so.

One small sentence about the required write sequence in the documentation would still make this a “surprise requirement”, but a documented one. Without any documentation, its pure luck if a client pushes the buttons in the right order or not.

If you want one learning from this story: If a failure happens only occassionally, think about concurrency problems and include all periphery (humans, too!) into your scenarios.