One of the most useful metrics to us in the Softwareschneiderei is “CRAP”. For java, it is calculated by the Crap4J tool and provided as an HTML report. The report gives you a rough idea whats going on in your project, but to really know what’s up, you need to look closer.

A closer look on crap

The Crap4J tool spits out lots of numbers, especially for larger projects. But from these numbers, you can’t easily tell some important questions like:

- Are there regions (packages, classes) with lots more crap than others?

- What are those regions?

So we thought about the problem and found it to be solvable by data visualization.

Enter CrapMap

If you need to use advanced data visualization techniques, there is a very helpful project called prefuse (which has a successor named flare for web applications). It provides an exhaustive API to visualize nearly everything the way you want to. We wanted our crap statistics drawn in a treemap. A treemap is a bunch of boxes, crammed together by a clever layouting strategy, each one representing data, for example by its size or color.

The CrapMap is a treemap where every box represents a method. The size gives you a hint of the method’s complexity, the color indicates its crappyness. Method boxes reside inside their classes’ boxes which reside in package boxes. That way, the treemap represents your code structure.

A picture worth a thousand numbers

This is a screenshot of the CrapMap in action. You see a medium sized project with few crap methods (less than one percent). Each red rectangle is a crappy method, each green one is an acceptable method regarding its complexity.

Adding interaction

You can quickly identify your biggest problem (in terms of complexity) by selecting it with your mouse. All necessary data about this method is shown in the bottom section of the window. The overall data of the project is shown in the top section.

If you want to answer some more obscure questions about your methods, try the search box in the lower right corner. The CrapMap comes with a search engine using your methods’ names.

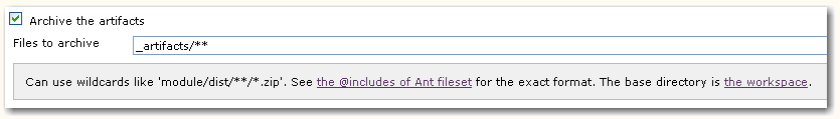

Using CrapMap on your project

CrapMap is a java swing application, meant for desktop usage. To visualize your own project, you need the report.xml data file of it from Crap4J. Start the CrapMap application and load the report.xml using the “open file” dialog that shows up. That’s all.

In the near future, CrapMap will be hosted on dev.java.net (crapmap.dev.java.net). Right now, it’s only available as a binary executable from our download server (1MB download size). When you unzip the archive, double-click the crapmap.jar to start the application. CrapMap requires Java6 to be installed.

Show your project

We would be pleased to see your CrapMap. Make a screenshot, upload it and leave a comment containing the link to the image.

In my rare spare time, I hold lectures on software engineering at the

In my rare spare time, I hold lectures on software engineering at the

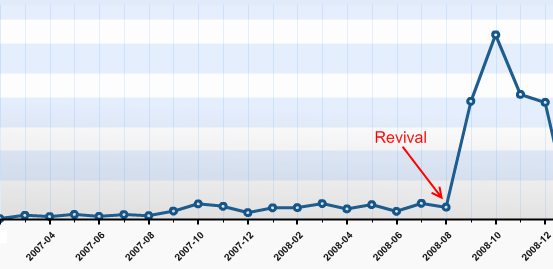

We started this blog in February 2007. Soon afterwards, it was nearly dead, as no new articles were written. Why? We would have answered to “be under pressure” and “have more relevant things to do” or simply “have no idea about what to write”. The truth is that we didn’t regard this blog as being important to us. We didn’t allocate any ressources, be it time, topics or attention to it. Seeming unimportant is a sure death cause for any business resource in any mindful managed company.

We started this blog in February 2007. Soon afterwards, it was nearly dead, as no new articles were written. Why? We would have answered to “be under pressure” and “have more relevant things to do” or simply “have no idea about what to write”. The truth is that we didn’t regard this blog as being important to us. We didn’t allocate any ressources, be it time, topics or attention to it. Seeming unimportant is a sure death cause for any business resource in any mindful managed company.