What causes a speedup like this? (all numbers are in ms)

Disclaimer: the absolute benchmark numbers are for illustration purposes, the relationship and the speedup between the different approaches are important (just for the curious: I measured 500 entries per table in a PostgreSQL database with both Rails 4.1.0 and Grails 2.3.8 running on Java 7 on a recent MBP running OSX 10.8)

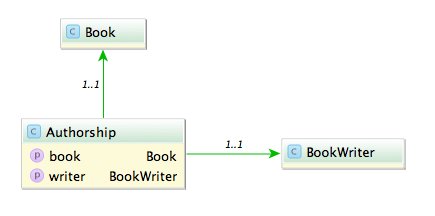

Say you have the model classes Book and (Book)Writer which are connected via a n x m table named Authorship:

A typical query would be to list all books with its authors like:

Fowler, Martin: Refactoring

A straight forward way is to query all authorships:

In Rails:

# 1500 ms

Authorship.all.map {|authorship| "#{authorship.writer.lastname}, #{authorship.writer.firstname}: #{authorship.book.title}"}

In Grails:

// 585 ms

Authorship.list().collect {"${it.writer.lastname}, ${it.writer.firstname}: ${it.book.title}"}

This is unsurprisingly not very fast. The problem with this approach is that it causes the famous n+1 select problem. The first option we have is to use eager fetching. In Rails we can use ‘includes’ or ‘joins’. ‘Includes’ loads the associated objects via additional queries, one for authorship, one for writer and one for book.

# 2300 ms Authorship.includes(:book, :writer).all

‘Joins’ uses SQL inner joins to load the associated objects.

# 1000 ms Authorship.joins(:book, :writer).all

# returns only the first element Authorship.joins(:book, :writer).includes(:book, :writer).all

Additional queries with ‘includes’ in our case slows down the whole request but with joins we can more than halve our time. The combination of both directives causes Rails to return just one record and is therefore ruled out.

In Grails using ‘belongsTo’ on the associations speeds up the request considerably.

class Authorship {

static belongsTo = [book:Book, writer:BookWriter]

Book book

BookWriter writer

}

// 430 ms

Authorship.list()

Also we can implement eager loading with specifying ‘lazy: false’ in our mapping which boosts a mild performance increase.

class Authorship {

static mapping = {

book lazy: false

writer lazy: false

}

}

// 416 ms

Authorship.list()

Can we do better? The normal approach is to use ‘has_many’ associations and query from one side of the n x m association. Since we use more properties from the writer we start from here.

class Writer < ActiveRecord::Base has_many :authors has_many :books, through: :authors end

Testing the different combinations of ‘includes’ and ‘joins’ yields interesting results.

# 1525 ms Writer.all.joins(:books) # 2300 ms Writer.all.includes(:books) # 196 ms Writer.all.joins(:books).includes(:books)

With both options our request is now faster than ever (196 ms), a speedup of 7.

What about Grails? Adding ‘hasMany’ and the authorship table as a join table is easy.

class BookWriter {

static mapping = {

books joinTable:[name: 'authorships', key: 'writer_id']

}

static hasMany = [books:Book]

}

// 313 ms, adding lazy: false results in 295 ms

BookWriter.list().collect {"${it.lastname}, ${it.firstname}: ${it.books*.title}"}

The result is rather disappointing. Only a mild speedup (2x) and even slower than Rails.

Is this the most we can get out of our queries?

Looking at the benchmark results and the detailed numbers Rails shows us hints that the query per se is not the problem anymore but the deserialization. What if we try to limit our created object graph and use a model class backed by a database view? We can create a view containing all the attributes we need even with associations to the books and writers.

create view author_views as (SELECT "authorships"."writer_id" AS writer_id, "authorships"."book_id" AS book_id, "books"."title" AS book_title, "writers"."firstname" AS writer_firstname, "writers"."lastname" AS writer_lastname FROM "authorships" INNER JOIN "books" ON "books"."id" = "authorships"."book_id" INNER JOIN "writers" ON "writers"."id" = "authorships"."writer_id")

Let’s take a look at our request time:

# 15 ms

AuthorView.select(:writer_lastname, :writer_firstname, :book_title).all.map { |author| "#{author.writer_lastname}, #{author.writer_firstname}: #{author.book_title}" }

// 13 ms

AuthorView.list().collect {"${it.writerLastname}, ${it.writerFirstname}: ${it.bookTitle}"}

13 ms and 15 ms. This surprised me a lot. Seeing this in comparison shows how much this impacts performance of our request.

The lesson here is that sometimes the performance can be improved outside of our code and that mapping database results to objects is a costly operation.