In my private game programming projects, I am often using data files alongside my code for all kinds of game assets like images and sounds. So I thought it might be a good idea to use the Git Large File Storage (=LFS) extension for that.

What is Git LFS?

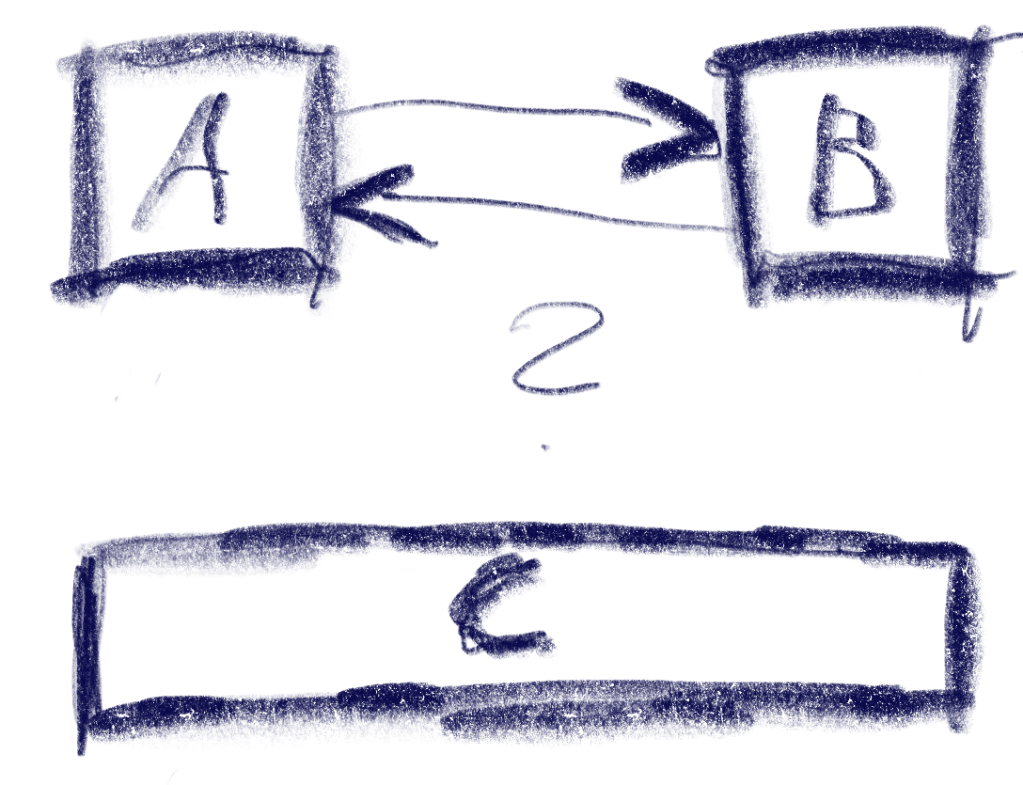

Essentially, if you’re not using it, the file will be in your local .git folder if it was part of your repository at any time in your history. E.g. if you accidentally added&committed a 800mb video files and then deleted it again, they will still be in your local .git folder. This problem multiplies when using a CI with many branches: each branch will typically have a copy of all files ever used in your repository. This is not a problem with source code files, because they are not that big and they can be compressed really well with different versions of themselves, which is what git typically does.

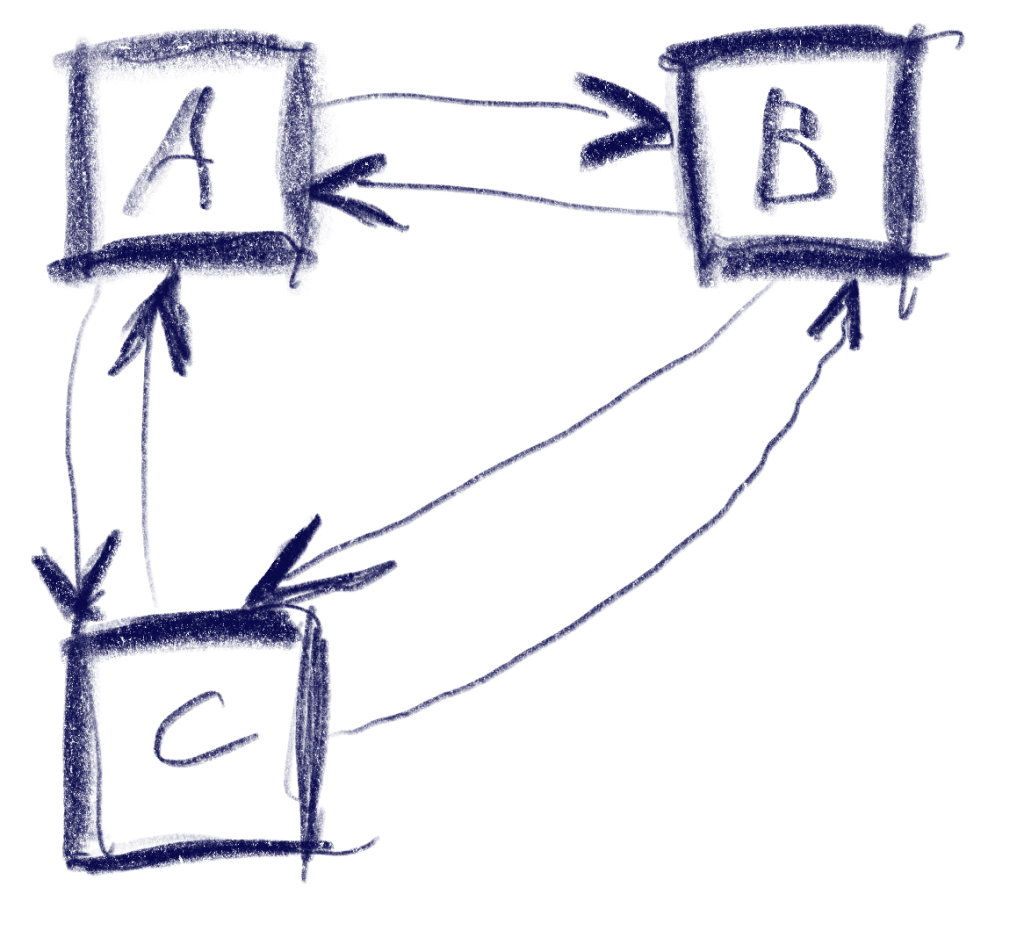

With Git LFS, the big files are only stored as references in the .git folder. This means that you might need an additional request to your remote when checking them out again, but it will save you lots space and traffic when cloning repositories.

In my previous projects on github, I just did not enable LFS for my assets. And that worked fine, as my assets are usually pretty small and I don’t change them often. But this time I wanted to try it.

Sorry, Github, what?

Imagine my suprise when I got an e-mail from github last month warning me that my LFS traffic quota is almost reached and I have to pay to extend it. What? I never had and traffic quota problems without LFS. Github doesn’t even seem to have one, if I just keep my big files in ‘pure’ git. So that’s what I get for trying to safe Github traffic.

Now the LFS quota is a meager 1 gb per month with Github Pro. That’s nothing. Luckily, my current project is not asset heavy: the full repo is very small at ~60mb. But still the quota was reached with me as a single developer. How did that happen? I just enabled CI for my project on my home server and I was creating lots of branches my CI wanted to build. That’s only 12 branches cloned for the 80% warning to be reached.

Workarounds

Jenkins, which I’m using as a CI tool, has the ability to use a ‘reference repository’ when cloning. This can be used to get the bulk of the data from a local remote, while getting the rest from Github. This is what I’m now using to avoid excess LFS traffic. It is a bit of a pain to set up: you have to manually maintain this reference repository, Jenkins will not do it for you, and you have to do that on each agent. I only have one at this point, so that’s an okay trade-off. But next time, Isure won’t use Git LFS on Github, if I can avoid it.