In part 1 of our series covering the RPM package management system we learned the basics and built a template SPEC file for packaging software. Now I want to give you some deeper advice on building packages for different openSUSE releases, architectures and build systems. This includes hints for projects using cmake, qmake, python, automake/autoconf, both platform dependent and independent.

Use existing makros and definitions

RPM provides a rich set of macros for generic access to directory paths and programs providing better portability over different operating system releases. Some popular examples are /usr/lib vs. /usr/lib64 and python2.6 vs. python2.7. Here is an exerpt of macros we use frequently:

%_liband%_libdirfor selection of the right directory for architecture dependent files; usually[/usr/]libor[/usr/]lib64.%py_sitedirfor the destination of python libraries and%py_requiresfor build and runtime dependencies of python projects.%setup,%patch[#],%configure,%{__python}etc. for preparation of the build and execution of helper programs.%{buildroot}for the destination directory of the build artifacts during the build

Use conditionals to enable building on different distros and releases

Sometimes you have to use %if conditional clauses to change the behaviour depending on

- operating system version

%if %suse_version < 1210 Requires: libmysqlclient16 %else Requires: libmysqlclient18 %endif

- operating system vendor

%if "%{_vendor}" == "suse" BuildRequires: klogd rsyslog %endif

because package names differ or different dependencies are needed.

Try to be as lenient as possible in your requirement specifications enabling the build on more different target platforms, e.g. use BuildRequires: c++_compiler instead of BuildRequires: g++-4.5. Depend on virtual packages if possible and specify the versions with < or > instead of = whenever reasonable.

Always use a version number when specifying a virtual package

RPM does a good job in checking dependencies of both, the requirements you specify and the implicit dependencies your package is linked against. But if you specify a virtual package be sure to also provide a version number if you want version checking for the virtual package. Leaving it out will never let you force a newer version of the virtual package if one of your packages requires it.

Build tool specific advices

- qmake: We needed to specify the

INSTALL_ROOTissuingmake, e.g.:qmake make INSTALL_ROOT=%{buildroot}/usr - autotools: If the project has a sane build system nothing is easier to package with RPM:

%build %configure make %install %makeinstall

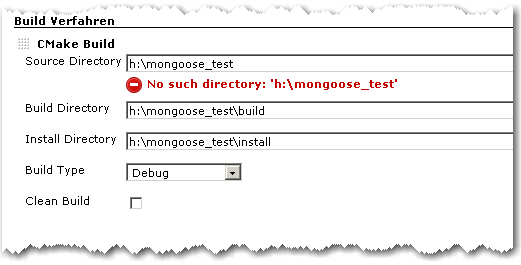

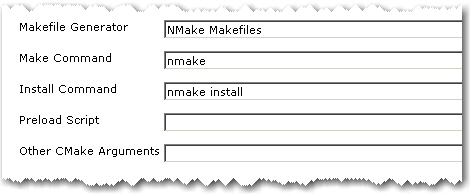

- cmake: You may need to specify some directory paths with -D. Most of the time we used something like:

%build cmake -DCMAKE_INSTALL_PREFIX=%{_prefix} -Dlib_dir=%_lib -G "Unix Makefiles" . make

Working with patches

When packaging projects you do not fully control, it may be neccessary to patch the project source to be able to build the package for your target systems. We always keep the original source archive around and use diff to generate the patches. The typical workflow to generate a patch is the following:

- extract source archive to

source-x.y.z - copy extracted source archive to a second directory:

cp -r source-x.y.z source-x.y.z-patched - make changes in

source-x.y.z-patched - generate patch with:

cd source-x.y.z; diff -Naur . ../source-x.y.z-patched > ../my_patch.patch

It is often a good idea to keep separate patches for different changes to the project source. We usually generate separate patches if we need to change the build system, some architecture or compiler specific patches to the source, control-scripts and so on.

Applying the patch is specified in the patch metadata fields and the prep-section of the SPEC file:

Patch0: my_patch.patch

Patch1: %{name}-%{version}-build.patch

...

%prep

%setup -q # unpack as usual

%patch0 -p0

%patch1 -p0

Conclusion

RPM packaging provides many useful tools and abstractions to build and package projects for a wide variety of RPM-based operation systems and releases. Knowing the macros and conditional clauses helps in keeping your packages portable.

In the next and last part of this series we will automate building the packages for different target platforms and deploying them to a repository server.