In the first part I emphasized how important it is to think for the user. Normally I tried to think like the user. The problem is: the users of my software have a totally different view point and experience. They are experts in their respective domain and have years of working knowledge in it. So I try a more naive approach: thinking with a beginner’s mind. Question everything. Get to the whys, the reasons. But how do I translate this information to a software interface?

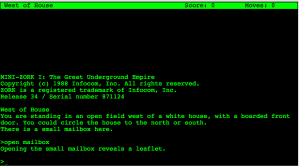

A text adventure

I remember playing (and programming) my first text adventures, later on with simple static images. Many of them had a rich and fascinating atmosphere in spite of having any graphic gizmos or sophisticated real time action.

One of the most important parts of your user interface is text and the words need to be carefully chosen from the user’s domain. But here I want to highlight another similarity between a text adventure and thinking for the user. A text adventure presents the user with a short but sufficient description. These small snippets of text is all the information the user needs at this step of his journey.

A user interface should be the same. Think about the crucial information the user needs at this step. But the description does not stop here: it highlights important parts which further the story. Think about the necessary information and the most important information. Think about a simple hierarchy of information.

For atmosphere and fun the text adventures add small sentences or even unusual phrasing. Besides highlighting things by contrast these parts help the user to get a sense where in the part of the journey he is. Where he came from and where he can go. It connects different rooms.

A business process from the user’s domain is like a journey through the software. He needs to know what the next steps are, what is expected and what is already accomplished. Furthermore the actions which can be done are of utmost importance. In text adventures objects which can be interacted with are emphasized by giving them an extra wording or sentence at the end of a paragraph. Actions are revealed by the domain (common wisdom or specific domain knowledge like fantasy).

For this we need to determine which actions can be done in this part of the process, on this screen.

Information and actions

After listening and reflecting on the information we collected from the user’s view point of their domain, we need to divide it up into steps of a process and form a consistent journey which resembles the imagination of the process the users have in mind. Ryan Singer uses a simple but effective notation for jotting down the needed information and the possible actions.

The information forms the base. Without it the user does not know where in the process he is, what process he works on and what are the next steps. In order to extract this information form the vast knowledge we already collected we need to abstract.

Imagine you have only the information present in this step and want to reach this goal. Is this possible? Is the information sufficient? What information is lacking? Is the missing information part of the common domain knowledge? Did you verify it is common domain knowledge? And if you have enough information: do you know what the expected actions are? What should be done to get further to the goal?

The big picture

Thinking about every step on the way to the goal helps designing each step. But it is also important to not lose sight of the big picture, the goal. Maybe some steps are not necessary or can be circumvented in special cases. Here you need the knowledge of the domain experts. But remember you need to question the assumptions behind their reasoning. Some steps may be mandated by law, some steps may be needed as a mental help. Do not try to cram everything into one step. The steps and their order need to resemble the mental image of the users. But you can help to remove cruft and maybe even delight them on their journey. But this is part of another post.