We are always in pursue of improving our build and development infrastructures. Who isn’t?

At Softwareschneiderei, we have about five times as many projects than we have developers (without being overworked, by the way) and each of that comes with its own requirements, so it is important to be able to switch between different projects as easily as cloning a git repository, avoiding meticulous configuration of your development machines that might break on any change.

This is the main advantage of the development container (DevContainer) approach (with Docker being the major contestant at the moment), and last November, I tried to outline my then-current understanding of integrating such an approach with the JetBrains IDEs. E.g. for WebStorm, there is some kind of support for dockerized run configurations, but that does some weird stuff (see below), and JetBrains did not care enough yet to make that configurable, or at least to communicate the sense behind that.

Preparing our Dev Container

In our projects, we usually have at least two Docker build stages:

- one to prepare the build platform (this will be used for the DevContainer)

- one to execute the build itself (only this stage copies actual sources)

There might be more (e.g. for running the build in production, or for further dependencies), but the basic distinction above helps us to speed up the development process already. (Further reading: Docker cache management)

For one of our current React projects (in which I chose to try Vite in favor of the outdated Create-React-App, see also here), the Dockerfile might look like

# --------------------------------------------

FROM node:18-bullseye AS build-platform

WORKDIR /opt

COPY package.json .

COPY package-lock.json .

# see comment below

RUN npm install -g vite

RUN npm ci --ignore-scripts

WORKDIR /opt/project

# --------------------------------------------

FROM build-platform AS build-stage

RUN mkdir -p /build/result

COPY . .

CMD npm run build && mv dist /build/result/app

The “build platform” stage can then be used as our Dev Container, from the command line as (assuming, this Dockerfile resides inside your project directory where also src/ etc. are chilling)

docker build -t build-platform-image --target build-platform .

docker run --rm -v ${PWD}:/opt/project <command_for_starting_dev_server>

Some comments:

- The RUN step to

npm install -g vite is required for a Vite project because the our chosen base image node:18-bullseye does not know about the vite binaries. One could improve that by adding another step beforehand, only preparing a vite+node base image and taking advantage of Docker caching from then on.

- We specifically have to take the

WORKDIR /opt/project because our mission statement is to integrate the whole thing with WebStorm. If you are not interested in that, that path is for you to choose.

Now, if we are not working against any idiosyncrasies of an IDE, the preparation step “npm ci” gives us all our node dependencies in the current directory inside a node_modules/ folder. Because this blog post is going somewhere, already now we chose to place that node_modules in the parent folder of the actual WORKDIR. This will work because for lack of an own node_modules, node will find it above (this fact might change with future Node versions, but for now it holds true).

The Challenge with JetBrains

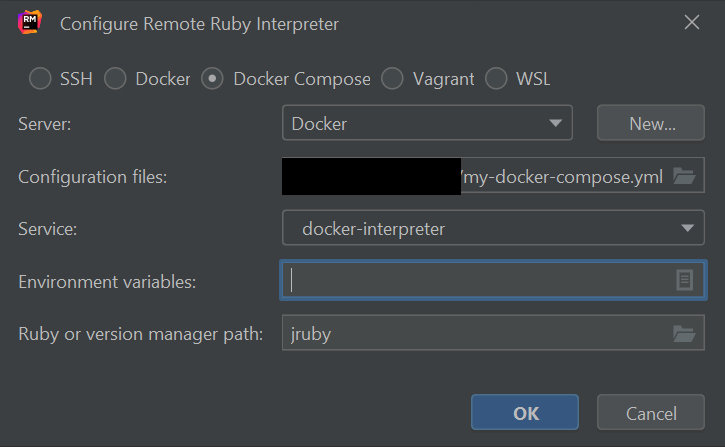

Now, the current JetBrains IDEs allow you to run your project with the node interpreter (containerized within the node-platform image) in the “Run/Debug Configurations” window via

“+” ➔ “npm” ➔ Node interpreter “Add…” ➔ “Add Remote” ➔ “Docker”

then choose the right image (e.g. build-platform-image:latest).

Now enters that strange IDE behaviour that is not really documented or changeable anywhere. If you run this configuration, your current project directory is going to be mounted in two places inside the container:

- /opt/project

- /tmp/<temporary UUID>

This mounting behaviour explains why we cannot install our node_modules dependencies inside the container in the /opt/project path – mounting external folders always override anything that might exist in the corresponding mount points, e.g. any /opt/project/node_modules will be overwritten by force.

As we cared about that by using the /opt parent folder for the node_modules installation, and we set the WORKDIR to be /opt/project one could think that now we can just call the development server (written as <command_for_starting_dev_server> above).

But we couldn’t!

For reasons that made us question our reality way longer than it made us happy, it turned out that the IDE somehow always chose the /tmp/<uuid> path as WORKDIR. We found no way of changing that. JetBrains doesn’t tell us anything about it. the “docker run -w / --workdir” parameter did not help. We really had to use that less-than-optimal hack to modify the package.json “scripts” options, by

"scripts": {

"dev": "vite serve",

"dev-docker": "cd /opt/project && vite serve",

...

},

The “dev” line was there already (if you use create-react-app or something else , this calls that something else accordingly). We added another script with an explicit “cd /opt/project“. One can then select that script in the new Run Configuration from above and now that really works.

We do not like this way because doing so, one couples a bad IDE behaviour with hard coded paths inside our source files – but at least we separate it enough from our other code that it doesn’t destroy anything – e.g. in principle, you could still run this thing with npm locally (after running “npm install” on your machine etc.)

Side note: Dealing with the “@esbuild/linux-x64” error

The internet has not widely adopteds Vite as a scaffolding / build tool for React projects yet and one of the problems on our way was a nasty error of the likes

Error: The package "esbuild-linux-64" could not be found, and is needed by esbuild

We found the best solution for that problem was to add the following to the package.json:

"optionalDependencies": {

"@esbuild/linux-x64": "0.17.6"

}

… using the “optionalDependencies” rather than the other dependency entries because this way, we still allow the local installation on a Windows machine. If the dependency was not optional, npm install would just throw an wrong-OS-error.

(Note that as a rule, we do not like the default usage of SemVer ^ or ~ inside the package.json – we rather pin every dependency, and do our updates specifically when we know we are paying attention. That makes us less vulnerable to sudden npm-hacks or sneaky surprises in general.)

I hope, all this information might be useful to you. It took us a considerable amount of thought and research to come to this conclusion, so if you have any further tips or insights, I’d be glad to hear from you!