but not with a song, only with an assertion failure. Okay, I’ll admit, this is not the only hyperbole in the blog title. Let’s set things right: The story didn’t happen last night, it didn’t even happen at night (because I’m not working night hours). In fact, it was a well-lit sunny day. And the test didn’t save my live. It did save me from some embarrassment, though. And spared a customer some trouble and hotfixing sessions with me.

The true parts of the blog title are: An end-to-end test reported an assertion failure that helped me to fix a bug before it got released. In other words: An end-to-end test did its job and I felt fine. And that’s enough of the obscure song references from the 1980s, hopefully.

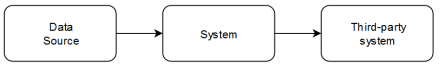

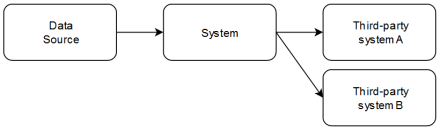

Let me explain the setting. We develop a big system that runs in production 24/7-style and is perpertually adjusted and improved. The system should run unattended and only require human attention when a real incident happens, either in the data or the system itself. If you look at the system from space, it looks like this:

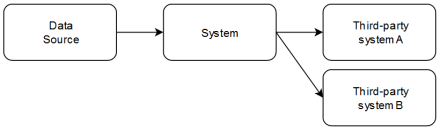

A data source (in fact, lots of data sources) occasionally transmits data to the system that gets transformed and sent to a third-party system that does all kind of elaborate analysis with it. Of course, there is more to the real system than that, but for our story, it is sufficient to know that there are several third-party systems, each with their own data formats. We’ll call them third-party system A (TPS-A) and TPS-B in this story.

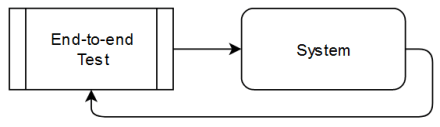

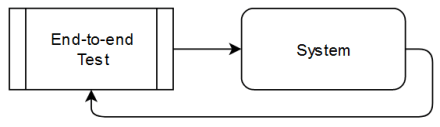

Our system is secured by lots and lots of unit tests, a good number of integration tests and a handful of end-to-end tests. All tests run green all the time. The end-to-end tests (E2ET) try to replicate the production environment as close as possible by running on the target operating system and using data transfer means like in the real case. The test boots up the complete system and simulates the data source and the third-party systems. By configuring the system so that it transfers back to the E2ET, we can write assertions in the kind of “given a specific input data, we expect this particular output data from the system, however it chooses to produce it”. This kind of broad-brush test is invalueable because it doesn’t care for specifics in the system. It only cares for output from the system.

This kind of E2ET is also difficult to write, complicated to run, prone to brittleness and obscure in its failure statement. If you write a three-line unit test, it is straight-forward, fast and probably pretty specific when it breaks: “This one thing that I’m testing is wrong now”. An E2ET as described here is like the Delphi Oracle:

- E2ET: “Somewhere in your system, something doesn’t work the way I like it anymore.”

- Developer: “Can you be more specific?”

- E2ET: “No, but here are 2000 lines of debug output that might help you on your quest for the cause.”

- Developer: “But I didn’t change anything.”

- E2ET: “Oh, in that case, it could as well be the weather or a slow network. Mind if I run again?”

This kind of E2ET is also rather slow and takes its sweet time resetting the workspace state, booting the system again and using prolonged timeouts for every step. So you wait several minutes for the E2ET to fail again:

- E2ET: “Yup, there is still something fishy with your current code.”

- Developer: “It’s the same code you let pass yesterday.”

- E2ET: “Well, today I don’t like it!”

- Developer: “Okay, let me dive into the debug output, then.”

Ten to twenty minutes pass.

- Developer: “Is it possible that you just choke on a non-free network port?”

- E2ET: “Yes, I’m supposed to wait for the system’s output on this port and cannot bind to it.”

- Developer: “You cannot bind to it because an instance of yourself is stuck in the background and holding onto the port.”

- E2ET: “See? I’ve told you there is something wrong with your system!”

- Developer: “This isn’t a problem with the system’s code. This is a problem with your code.”

- E2ET: “Hey! Don’t blame me! I’m here to help. You can always chose to ignore or delete me if I’m too much of a burden to you.”

This kind of E2ET cries wolf lots of times for problems in the test code itself, for too optimistic timeouts or just oddities in the environment. If such an E2ET fails, it’s common practice to run it again to see if the problem persists.

How many false alarms can you tolerate before you stop listing?

In my case, I choose to reduce the amount of E2ET to the essential minimum and listen to them every time. If the test raises a false alarm, invest the time to come up with a way to make it more robust without reducing its sensitivity. But listen to the test every time.

Because, in my story, the test insisted that third-party system A and B both didn’t receive half of their data. I could rule out stray effects in the network or on the harddisk pretty fast, because the other half of the data arrived just fine. So I invested considerable time in understanding the debug output. This led me nowhere – it seemed that the missing data wasn’t sent to the system in the first place. Checking the E2ET disproved this hypothesis. The test sent as much data to the system as ever. But half of it went missing underway. Now I reviewed all changes I made in the last few days. Some of them affected the data export to the TPS. But all unit and integration tests in this area insisted that everything worked as intended.

It is important to have this kind of “multiple witnesses”. Unit tests are like traces in a criminal investigation: They report one very specific information about one very specific part of the code and are only useful in larger numbers. Integration tests testify on the possibility to combine several code parts. In my case, this meant that the unit tests guaranteed that all parts involved in the data export work correct on their own (in isolation). The integration tests vouched that, given the right combination of data export parts, they will work as intended.

And this left one area of the code as the main suspect: Something in the combination of export parts must go wrong in the real case. The code that wires the parts together is the only code not tested by unit and integration tests, but E2ET. Both other test types base their work on the hypothesis of “given that everything is wired together like this”. If this hypothesis doesn’t hold true in the real case, no test but the E2ET finds a problem, because the E2ET bases on another hypothesis: “given that the system is started for real”.

I went through all the changes of the wiring code and there it was: A glorious TODO comment, written by myself on a late friday afternoon, stating: “TODO: Register format X export again after you’ve finished issue Y”. I totally forgot about it over the weekend. I only added the comment into the code, not as an issue comment. Friday afternoon me wasn’t cooperative with future or current me. In effect, I totally played myself. I don’t remember removing the registering code or writing the comment. It probably was a minor side change for an unimportant aspect of the main issue. The whole thing was surely done in a few seconds and promptly forgotten. And the only guardian that caught it was the E2ET, using the most nonspecific words for it (“somewhere, something went wrong”).

If I had chosen to ignore or modify the E2ET, the bug would have made it to production. It would have caused a loss of current data for the TPS. Maybe they would have detected it. But maybe, they would have just chosen to operate on the most recent data – data that doesn’t get updated anymore. In short, we don’t want to find out.

So what is the moral of the story?

Always have an end-to-end test for your most important functionality in place. Let it deal with your system from the outside. And listen to it, regardless of the effort it takes.

And what can you do if your E2ET has saved you?

- Give your test a medal. No, seriously, leave a comment in the test code that it was helpful.

- Write an unit or integration test that replicates the specific cause. You want to know immediately if you make the same error again in the future. Your E2ET is your last line of defense. Don’t let it be your only one. You’ve been shown a weakness in your test setup, remediate it.

- Blame past you for everything. Assure future you that you are a better developer than this.

- Feel good that you were able to neutralize your faux pas in time. That’s impressive!

When was the last time a test has saved you? Leave the story or a link to it in the comments. I can’t be the only one.

Oh, and if you find the random links to 80s music videos weird: At least I didn’t rickroll you. The song itself is from 1987 and would fit my selection.