You might know this from fantasy book series: the author creates a unique world, a whole universe of their own and sets a story or series of books within it. Then, a few years later, a new series is released. It is set in the same universe, but at a different time, with different characters, and tells a completely new story. Still, it builds on the foundation of that original world. The author does not reinvent everything from scratch. They use the same map, the same creatures, the same customs and rules established in the earlier books.

Examples of this are the Harry Potter series and Fantastic Beasts, or The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit.

But what does this have to do with software development?

In one of my projects, I faced a very similar use case. I had to implement several services, each covering a different use case, but all sharing the same set of peripherals, adapters, and domain types.

So I needed an architecture that did not just allow for interchangeable periphery, as is usually the focus, but also supported interchangeable use cases. In other words, I needed a setup that allowed for multiple “books” to be written within the same “universe.”

Architecture

Let’s start with a simple example: user management.

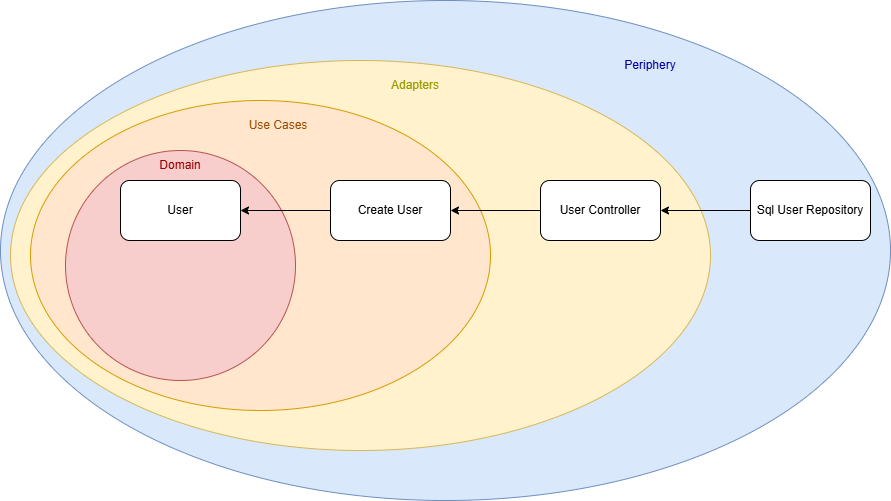

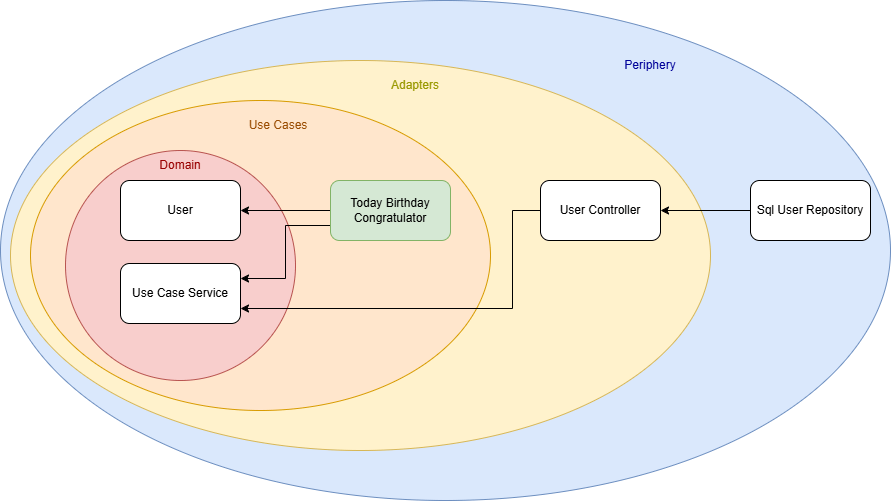

I originally implemented it following Clean Architecture principles, where the structure resembles an onion, dependencies flow inward, from the outer layers to the core domain logic. This makes the outer layers (the “peel”) easily replaceable or extendable.

Our initial use case is a service that creates a user. The use case defines an interface that the user controller implements, meaning the dependency flows from the outer layer (the controller) toward the core. So far, so good.

However, I wanted to evolve the architecture to support multiple use cases. For that, the direct dependency from the UserController to the CreateUser use case had to be removed.

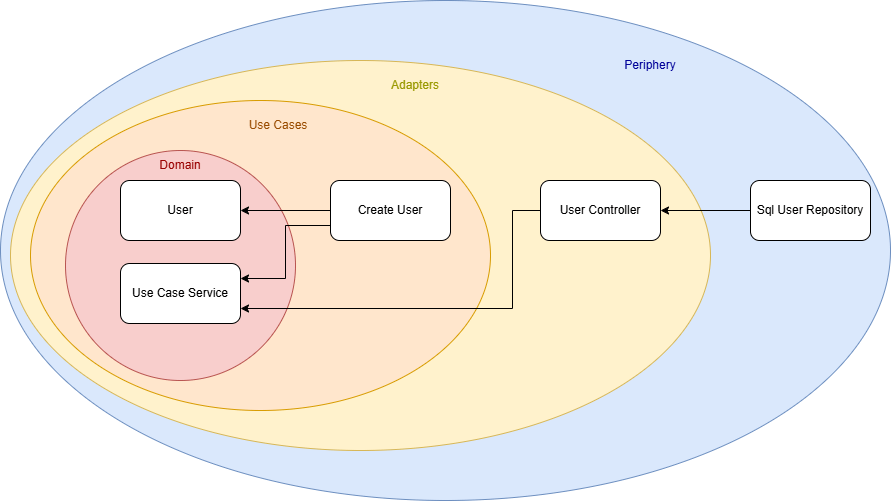

My solution was to introduce a new domain module, a shared foundation that contains all interfaces, data types, and common logic used by both use cases and adapters. I called this module the UseCaseService.

The result is a new architecture diagram:

There is no longer a direct connection between a specific use case and an adapter. Instead, both depend on the shared UseCaseService

For example, I could implement another service that retrieves all users whose birthday is today and sends them birthday greetings. (Whether this is GDPR-compliant is another discussion!) But thanks to this architecture, I now have the freedom to implement that use case cleanly and efficiently.

Conclusion

Architecture is a highly individual matter. There is no one-size-fits-all solution that solves every problem or suits every project. Models like Clean Architecture can be helpful guides, but ultimately, you need to define your own architectural requirements and find a solution that meets them. This was a short story of how one such solution came to life based on my own needs.

It is also a small reminder to keep the freedom to think outside the box. Do not be afraid to design an architecture that truly fits you and your project, even if it deviates from the standard models.