Slow down

Technology demands speed. Our industry focuses on speed and efficiency. Even our processes measure speed. (Scrum calls it velocity) But thinking needs time. Planning takes time. Caring needs time. Details need time. Testing needs time. Hearing, researching, observing, listening. All these need time. Designers know this.

We need to slow down. In order to see and design the details without losing the big picture we need to slow down. Great designs come from thinking hard. How do you do that? You concentrate on the essence. What matters most. How do you identify the essence? By thinking hard. And that needs time.

Design is about intention

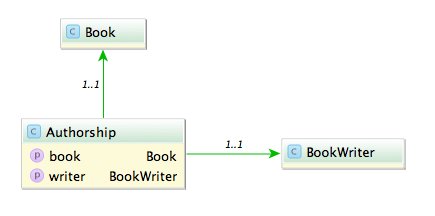

Take a look at your code: is every line there for a reason? Every line? The order of the methods. The name of the variables. The separation in classes, interfaces, packages. How much of it is accidentally? Good designers choose everything with a reason. The place of this button? No coincidence. This color? This control? This flow of actions? Everything has an intention behind it. The information presented. Even the information not presented. The wording? Is part of the overall character. The menu structure? Grounded in good decisions.

On the other side when I look at my code (especially after some months) it doesn’t look so organized and determined. The order of the methods? Grown. The reason for this interface when there is only one implementation? Maybe I thought there would be more. Using this pattern here? What part of your code tells you its intent? And how much cries: incidental complexity? Think about it: did you choose what to include and what to left out?

Test for change, build to learn

What was the subtitle of the first XP book? Embrace change. This sounds like we are victims. Change is coming and we need to cope with it. But what when change is really coming? Are we prepared? 58 unit tests for the garbage?! The whole architecture and patterns I developed, tested and refactored countless times? Delete them?! In reality we still fear change.

But it does not have to be this way. What do designers do? They test for change. They build wireframes, mockups, prototypes. If some of them didn’t work out they can abandon them. The cost to create them is low. And even when it was not the right design they learned something. They build the prototypes to test their hypotheses. They build them to proof or falsify their assumptions. They build to learn.

The learning effect is more important than the artifact itself.

And when the application is in production? They also test for change. They do A/B tests (again for learning). Designers don’t wait until change comes to them and then they have to embrace it, they test for change.

Listen

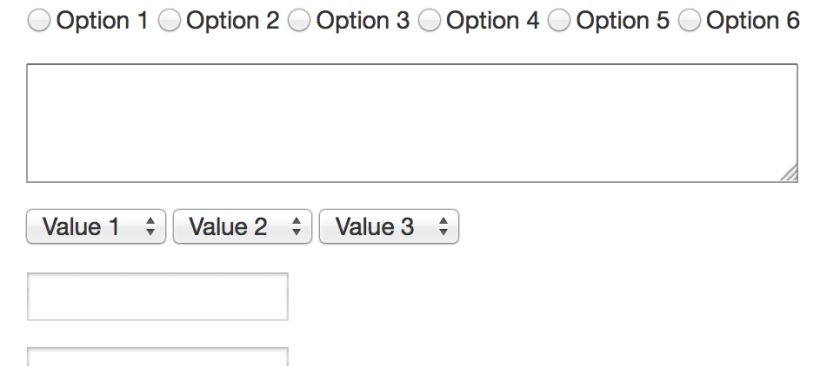

Listen. Truly listen. Shut down your preconceptions. How often do we ask too fast, too much? Suggestive questions? Questions with constrained possibilities to answer? I often ask goal directed questions. To further find out. To define what the requirements are.

Then one day I made a mistake. I asked an open ended question. And got an answer. Not what I expected. I thought I would know the shape of the problem. I thought: okay, we need a chart, the possibility to switch between different scales and a second view for the deviation. But no. Suddenly the customer tells me: just show one series in one scale. The deviation can be displayed in a table. We do not need other scales. In previous meetings he nodded in agreement when I presented the other solution. What happened? Did the customer change his mind? No. He told me his thoughts. Not the other way around. I did not tell him what I think and he agrees. He had to think for himself. He had to shape his thoughts in order to explain them to me. He had to think it through.

Net effect matters most

Developers like to think in features. When you ask a developer what did you do for customer X, he might tell you: we created a system to manage the complex process of submitting proposals for a great variety of technologies in an efficient manner. Features: submission of proposals, complexity management, flexibility and efficiency. The what.

A designer might answer: through our work scientists all over the world have access to advanced technology to explore the future of science. The effect on the world, users and customers.

Think what is made possible through our creations, how it improves lives. Start with why.

Documentation is essential

There is this notion in our craft that the code is all the documentation you need. Why is this the way it is? Take a look at the code. The code is the documentation. Look at the commit message. This is all you need.

No. In our experience code as documentation sucks. It is too low level. What is the goal you want to reach with this piece? What is the information you collected. What are the decisions you made. What is omitted. What is rethought. What alternatives were abandoned.

Designers use all kind of artifacts to learn and record their findings and decisions. They create and keep only the essential ones and keep it pragmatic. Easy to create. Easy to update. Easy to note down what you learned and what was wrong in your assumptions. The code is just one level of abstraction and usually the end result of the thought and decision process. Record and keep the way of the decisions, not just the end result.

Focus on the whole

Developers like to divide and conquer. To separate everything into small manageable pieces. Agile demands that. First services. Then microservices. What’s next? Nanoservices?

Designers on the other hand keep the complete experience in mind. For them the whole product matters. The whole is more than the sum of its parts. The dream of the developer is that all pieces fit like Lego stones together in the end. But they forget to imagine and plan the whole creation they wanted to build. A house is not the same as another house. The composition of rooms matter. The lighting. The connections between rooms and floors. The placement of windows and doors. The whole experience. The same is valid for applications that people use.

Solution alternatives

As developers we are natural problem solvers. We are given a problem and create a solution. Designers are problem solvers, too. They identify a problem and create many solutions, test them, rate them and present them. They explore. They test and learn. They collect data and evidence. They know that every solution has its trade offs. The most promising ones are evaluated. With a plan. With hypotheses. They crave for feedback.

Reduced and emphasized – It’s about the connection

YAGNI. KISS. We know them. But what do we do with the time saved? We solve other problems. Designers carve out the details. They think of interactions, clear wording, better defaults. The little things that delight the user. Going the extra mile. The user of the applications feels cared for. He feels that there was a human that thought about his situation. There’s a connection between designers and users through the application.

When we saw Bret Victor presenting his jaw dropping talk about “Inventing on principle” he made one important point: creators must feel a connection to their creation. I think everyone should feel a connection to the software he uses. He should feel cared for and delighted. Applications are not just tools, they are experiences, they create emotions, they connect us.