Anyone who has ever gone through a public tender knows the feeling: forms on forms, references to other forms, appendices that depend on annexes, and fields that must be filled exactly as specified somewhere on page 37 of a different document. This is not a task; it is a paper war.

Trying to fight this war alone is a mistake.

We learned that the most effective way to survive such bureaucratic battles is to treat them like a team sport. Not a big team—three people are enough—but with clearly defined roles.

The Problem with the Lone Warrior

The naive approach is simple: one person sits down, opens all documents, and starts filling things out.

This person must:

- understand the overall structure of the process,

- search for the right documents and sections,

- enter data correctly and consistently,

- double-check everything afterward.

That is a lot of cognitive load. The result is usually slow progress, rising frustration, and errors that only show up when it’s already too late.

The paper war doesn’t reward heroics. It rewards coordination.

A Three-Person Setup

We had much better results by splitting the work into three distinct roles, all active at the same time.

1. The EXECUTOR

The executor is the only person who actually enters data into the forms.

This role is deliberately narrow:

- type exactly what is agreed upon,

- do not search,

- do not interpret,

- do not “improve” anything on the fly.

The executor’s job is flow. By removing all other responsibilities, they can focus on speed and accuracy.

2. The Navigator

The navigator owns the overview.

They know:

- which document is relevant right now,

- where a specific field is defined,

- which appendix explains which requirement.

While the executor is typing, the navigator is already preparing the next reference: “Next field is in document B, section 4.2, and it depends on the value we used earlier in A.3.”

This prevents context switching for the executor and keeps the process moving forward.

3. The Checker

The checker validates everything live.

They verify:

- numbers,

- names,

- dates,

- consistency with previous entries,

- alignment with external sources (contracts, invoices, registers).

This is crucial: checking after the fact is expensive. Checking while data is entered is cheap. Errors are caught immediately, while the context is still fresh.

Like a Car Driving Lesson

This setup is not unfamiliar if you think about a car driving lesson.

The executor is the driver. They focus entirely on operating the vehicle: steering, braking, accelerating. They don’t decide where to go next; they just execute cleanly and safely.

The navigator is the driving instructor sitting in the passenger seat. They know the route, anticipate upcoming turns, and give timely instructions so the driver can react without stress.

The checker plays the role of the driving examiner in the back seat. Quiet but attentive, they observe everything, immediately spotting mistakes, inconsistencies, or rule violations before they become real problems.

Just like in a driving lesson, separating these roles creates confidence, flow, and control—exactly what you need when navigating bureaucratic traffic.

Why This Works

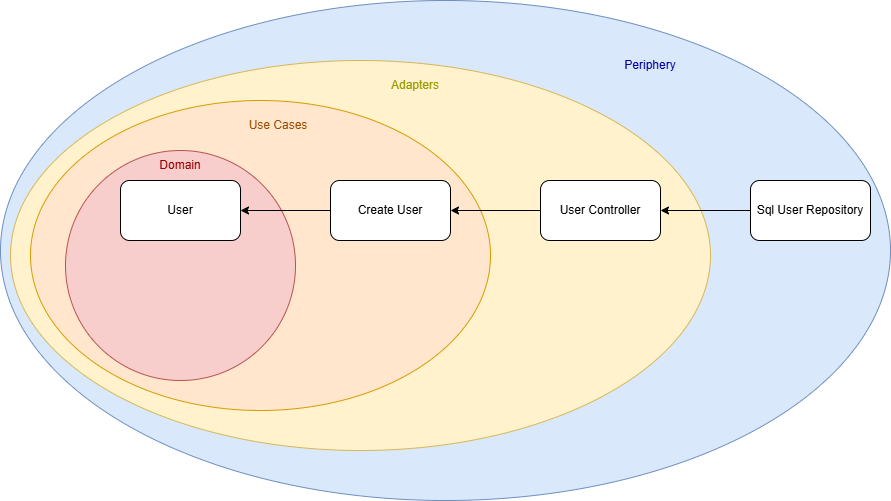

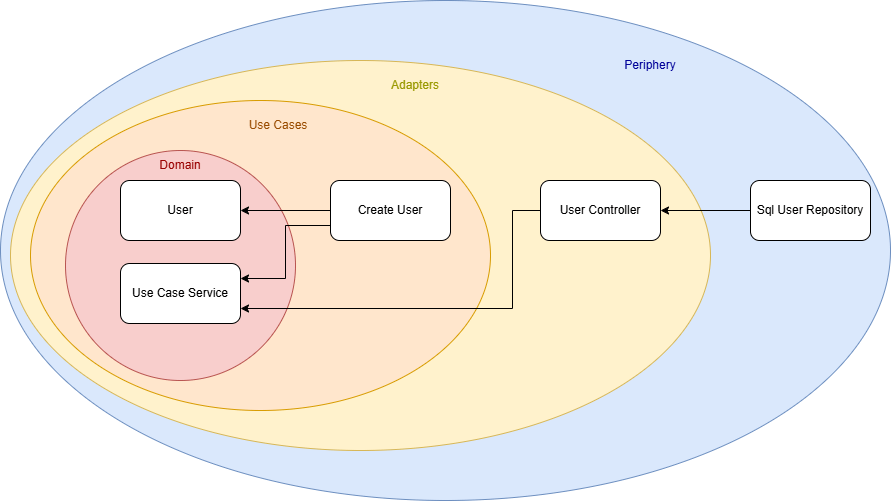

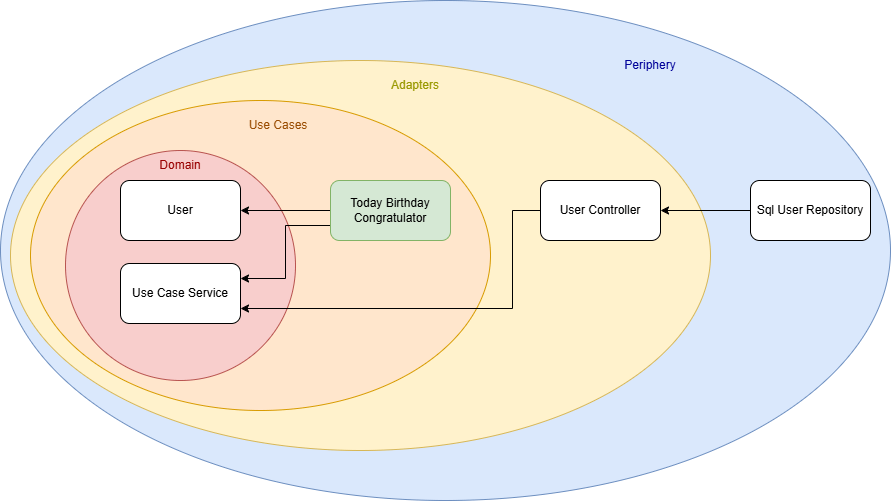

This setup mirrors patterns we already know from software development:

- separation of concerns,

- reducing cognitive load,

- fast feedback loops.

Each person has a clear responsibility, and overlaps are intentional but limited. Nobody is idle, and nobody is overwhelmed.

Most importantly, the process becomes predictable. Instead of a chaotic scramble through documents, you get a steady, almost mechanical flow from field to field.

Paper Wars Won’t Disappear

Bureaucratic processes are unlikely to become simpler anytime soon. Digital forms often just move the paper war onto a screen without changing its nature.

But how we approach them can change.

Treating a public tender as a collaborative, real-time effort instead of a solitary endurance test turns frustration into something manageable—and sometimes even efficient.

You may not win the war forever.

But at least you’ll win this battle.