When dividing decimal numbers in Java, some values—like 1 divided by 3—result in an infinite decimal expansion. In this blog post, I’ll show how such a calculation behaves using BigDecimal and BigFraction.

BigDecimal

Since this cannot be represented exactly in memory, performing such a division with BigDecimal without specifying a rounding mode leads to an “java.lang.ArithmeticException: Non-terminating decimal expansion; no exact representable decimal result”. Even when using MathContext.UNLIMITED or an effectively unlimited scale, the same exception is thrown, because Java still cannot produce a finite result.

BigDecimal a = new BigDecimal("1");

BigDecimal b = new BigDecimal("3");

BigDecimal c = a.divide(b);

By providing a scale – not MathContext.UNLIMITED – and a rounding mode, Java can approximate the result instead of failing. However, this also means the value is no longer mathematically exact. As shown in the second example, multiplying the rounded result back can introduce small inaccuracies due to the approximation.

BigDecimal a = new BigDecimal("1");

BigDecimal b = new BigDecimal("3");

BigDecimal c = a.divide(b, 100, RoundingMode.HALF_UP); // 0.3333333...

BigDecimal a2 = c.multiply(b); // 0.9999999...

When working with BigDecimal, it’s important to think carefully about the scale you actually need. Every additional decimal place increases both computation time and memory usage, because BigDecimal stores each digit and carries out arithmetic with arbitrary precision.

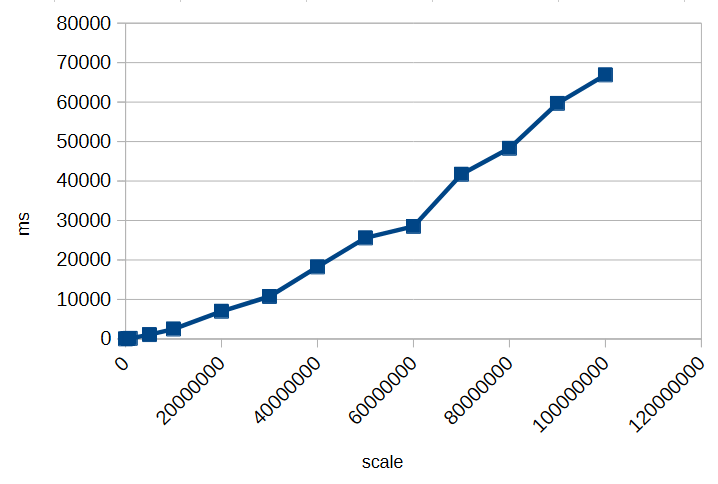

To illustrate this, here’s a small timing test for calculating 1/3 with different scales:

As you can see, increasing the scale significantly impacts performance. Choosing an unnecessarily high scale can slow down calculations and consume more memory without providing meaningful benefits. Always select a scale that balances precision requirements with efficiency.

However, as we’ve seen, decimal types like BigDecimal can only approximate many numbers when their fractional part is infinite or very long. Even with rounding modes, repeated calculations can introduce small inaccuracies.

But how can you perform calculations exactly if decimal representations can’t be stored with infinite precision?

BigFraction

To achieve truly exact calculations without losing precision, you can use fractional representations instead of decimal numbers. The BigFraction class from Apache Commons Numbers stores values as a numerator and denominator, allowing it to represent numbers like 1/3 precisely, without rounding.

import org.apache.commons.numbers.fraction.BigFraction;

BigFraction a = BigFraction.ONE;

BigFraction b = BigFraction.of(3);

BigFraction c = a.divide(b); // 1 / 3

BigFraction a2 = c.multiply(b); // 1

In this example, dividing 1 by 3 produces the exact fraction 1/3, and multiplying it by 3 returns exactly 1. Since no decimal expansion is involved, all operations remain mathematically accurate, making BigFraction a suitable choice when exact arithmetic is required.

BigFraction and Decimals

But what happens if you want to create a BigFraction from an existing decimal number?

BigFraction fromDecimal = BigFraction.from(2172.455928961748633879781420765027);

fromLongDecimal.bigDecimalValue(); // 2172.45592896174866837100125849246978759765625

At first glance, everything looks fine: you pass in a precise decimal value, BigFraction accepts it, and you get a fraction back. So far, so good. But if you look closely at the result, something unexpected happens—the number you get out is not the same as the one you put in. The difference is subtle, hiding far to the right of the decimal point—but it’s there.

And there’s a simple reason for it: the constructor takes a double.

A double cannot represent most decimal numbers exactly. The moment your decimal value is passed into BigFraction.from(double), it is already approximated by the binary floating-point format of double. BigFraction then captures that approximation perfectly, but the damage has already been done.

Even worse: BigFraction offers no alternative constructor that accepts a BigDecimal directly. So whenever you start from a decimal number instead of integer-based fractions, you inevitably lose precision before BigFraction even gets involved. What makes this especially frustrating is that BigFraction exists precisely to allow exact arithmetic.

Creating a BigFraction from a BigDecimal correctly

To preserve exactness when converting a BigDecimal to a BigFraction, you cannot rely on BigFraction.from(double). Instead, you can use the unscaled value and scale of the BigDecimal directly:

BigDecimal longNumber = new BigDecimal("2172.455928961748633879781420765027");

BigFraction fromLongNumber = BigFraction.of(

longNumber.unscaledValue(),

BigInteger.TEN.pow(longNumber.scale())

); // 2172455928961748633879781420765027 / 1000000000000000000000000000000

fromLongNumber.bigDecimalValue() // 2172.455928961748633879781420765027

This approach ensures the fraction exactly represents the BigDecimal, without any rounding or loss of precision.

BigDecimal longNumber = new BigDecimal("2196.329071038251366120218579234972");

BigFraction fromLongNumber = BigFraction.of(

longNumber.unscaledValue(),

BigInteger.TEN.pow(longNumber.scale())

); // 549082267759562841530054644808743 / 250000000000000000000000000000

fromLongNumber.bigDecimalValue() // 2196.329071038251366120218579234972

In this case, BigFraction automatically reduces the fraction to its simplest form, storing it as short as possible. Even though the original numerator and denominator may be huge, BigFraction divides out common factors to minimize their size while preserving exactness.

BigFraction and Performance

Performing fractional or rational calculations in this exact manner can quickly consume enormous amounts of time and memory, especially when many operations generate very large numerators and denominators. Exact arithmetic should only be used when truly necessary, and computations should be minimized to avoid performance issues. For a deeper discussion, see The Great Rational Explosion.

Conclusion

When working with numbers in Java, both BigDecimal and BigFraction have their strengths and limitations. BigDecimal allows precise decimal arithmetic up to a chosen scale, but it cannot represent numbers with infinite decimal expansions exactly, and high scales increase memory and computation time. BigFraction, on the other hand, can represent rational numbers exactly as fractions, preserving mathematical precision—but only if constructed carefully, for example from integer numerators and denominators or from a BigDecimal using its unscaled value and scale.

In all cases, it is crucial to be aware of these limitations and potential pitfalls. Understanding how each type stores and calculates numbers helps you make informed decisions and avoid subtle errors in your calculations.