Just yesterday, I was working on the task of enabling gamepad navigation of a graphical UI. I had implemented this before in my game abstractanks but since forgotten how exactly I did it. So I opened the old code and tried to decipher it, and I figured that’d make a nice topic to write about.

Basic implementation

Let’s break down the simple version of the problem: You have a bunch of rectangular controls, and given a specific one, figure out the next one with an input of either left, up, right or down.

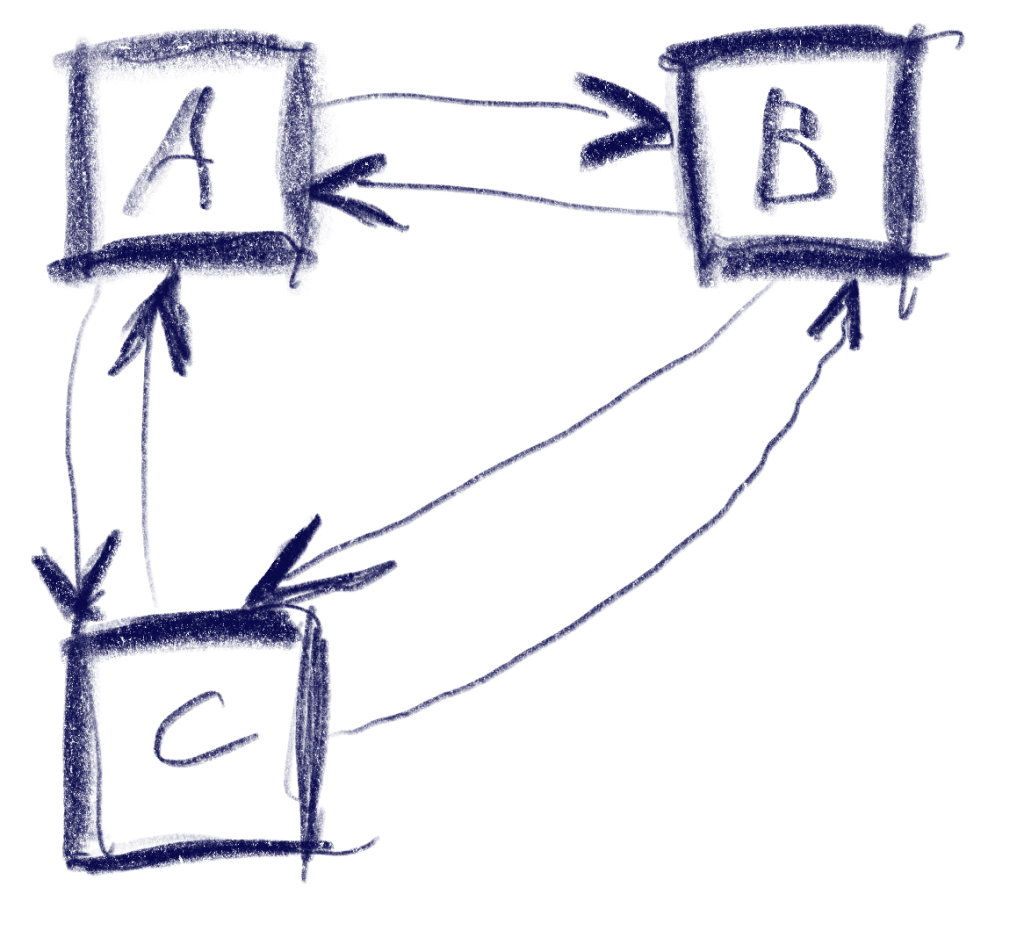

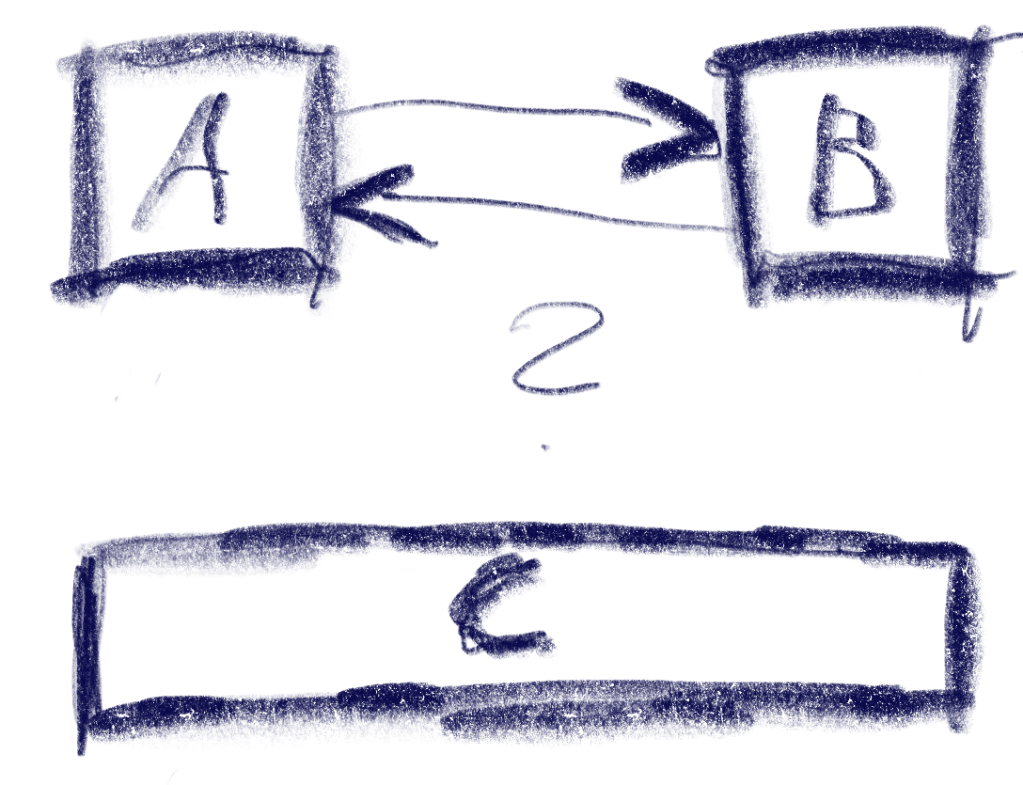

This sketch shows a control setup with a possible solution. It also contains an interesting situation: going ‘down’ from B box goes to C, but going up from there goes to A!

The key to creating this solution is a metric that weights the gap for a specific input direction, e.g. neighbor_metric(

box<> const& from, box<> const& to, navigation_direction direction). To implement this, we need to convert this gap into numbers we can use. I’ve used a variant of Arvo’s algorithm for that: For both axes, get the difference of the rectangles’ intervals along that axis and store those in a 2d-vector. In code:

template <int axis> inline float difference_on_axis(

box<> const& from, box<> const& to)

{

if (to.min[axis] > from.max[axis])

return to.min[axis] - from.max[axis];

else if (to.max[axis] < from.min[axis])

return to.max[axis] - from.min[axis];

return 0.f;

}

v2<> arvo_vector(box<> const& from, box<> const& to)

{

return {

difference_on_axis<0>(from, to),

difference_on_axis<1>(from, to) };

}

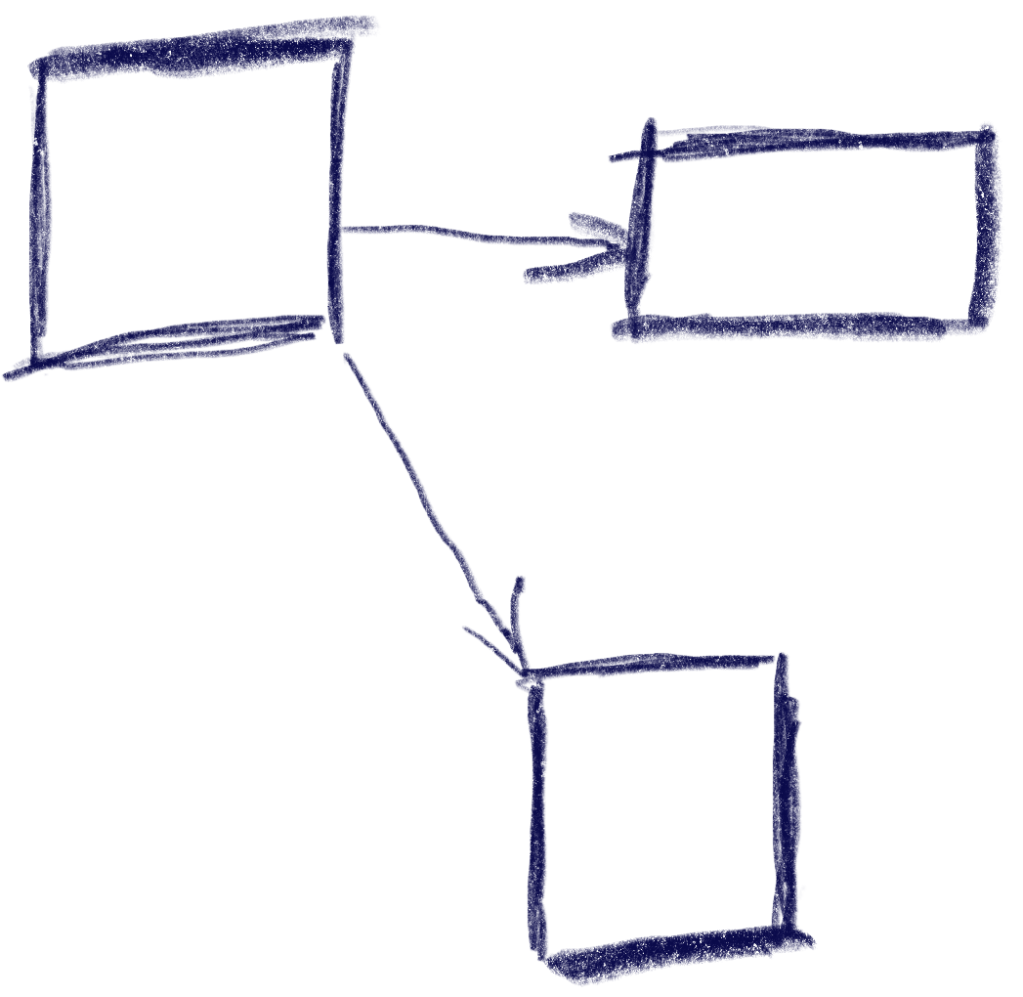

That sketch shows the resulting vectors from the box in the top-left going to two other boxes. Note that these vectors are quite different from the difference of the boxes’ centers. In the case of the two top boxes, the vector connecting the centers would tilt down slightly, while this one is completely parallel to the x axis.

Now armed with this vector, let’s look at the metric I was using. It results in a 2d ‘score’ that is later compared lexicographically to determine the best candidate: the first number determines the ‘angle’ with the selected axis, the other one the distance.

template <int axis> auto metric_on_axis(box<> const& from, box<> const& to)

{

auto delta = arvo_vector(from, to);

delta[0] *= delta[0];

delta[1] *= delta[1];

auto square_distance = delta[0] + delta[1];

float cosine_squared = delta[axis] / square_distance;

return std::make_pair(-cosine_squared, delta[axis]);

}

std::optional<std::pair<float, float>> neighbor_metric(

box<> const& from, box<> const& to, navigation_direction direction)

{

switch (direction)

{

default:

case navigation_direction::right:

{

if (from.max[0] >= to.max[0])

return {};

return metric_on_axis<0>(from, to);

}

case navigation_direction::left:

{

if (from.min[0] <= to.min[0])

return {};

return metric_on_axis<0>(from, to);

}

case navigation_direction::up:

{

if (from.max[1] >= to.max[1])

return {};

return metric_on_axis<1>(from, to);

}

case navigation_direction::down:

{

if (from.min[1] <= to.min[1])

return {};

return metric_on_axis<1>(from, to);

}

}

}

In practice this means that the algorithm will favor connections that best align with the input direction, while ties resolved by using the closest candidate. The metric ‘disqualifies’ candidates going backward, e.g. when going right, the next box cannot start left of the from box.

Now we just need to loop through all candidates and the select the one with the lowest metric.

This algorithm does not make any guarantees that all controls will be accessible, but that is a property that can easily be tested by traversing the graph induced by this metric, and the UI can be designed appropriately. It also does not try to be symmetric, e.g. going down then up does not always result in going back to the previous control. As we can see in the first sketch, this is not always desirable. I think it’s nice to be able to go from B to C via ‘down’, but I’d be weird to go ‘up’ back there instead of A. Instead, going ‘right’ to B does make sense.

Hard cases

But there can be ambiguities that this algorithm does not quite solve. Consider the case were C is wider, so that is is also under B:

The algorithm will connect both A and B down to C, but the metric will be tied for A and B going up from C. The metric could be extended to also include the ‘cross’ axis min-point of the box, e.g. favoring left over right for westerners like me. But going from B down to C and then up to A would feel weird. One idea to resolve this is to use the history to break ties, e.g. when coming from B to C, going back up would go back to C.

Another hard case is scroll-views. In fact, they seem to change the problem domain. Instead of treating the inputs as boxes in a flat plane, navigating in a scroll view requires to navigate to potentially only partially visible or even invisible boxes and bringing them into view. I’ve previously solved this by treating every scroll-view as its own separate plane and navigating only within that if possible. Only when no target is found within the scroll-view, did the algorithm try to navigate to items outside.