The most striking feature of WPF is its peculiar understanding of flexibility. Which means, that usually you are free to do anything, anywhere, but it instantly hands back to you the responsibility to pay super-close attention of where you actually are.

As projects with grow, their user interfaces usually grow, and over time there usually appears the need to re-use any given component of that user interface.

This not only is the working of the DRY principle at the code level, Consistency is also one of the Nielsen-Norman Usability Heuristics, i.e. a good plan as to not confuse your users with needless irritations. This establishes trust. Good stuff.

Now say that you have a re-usable custom button that should

- Look a certain way at a given place,

- Show custom interactivity (handling of mouse events)

- Be fully integrated in the XAML workflow, especially accepting Bindings from outside, as inside an ItemsControl or other list-type Control.

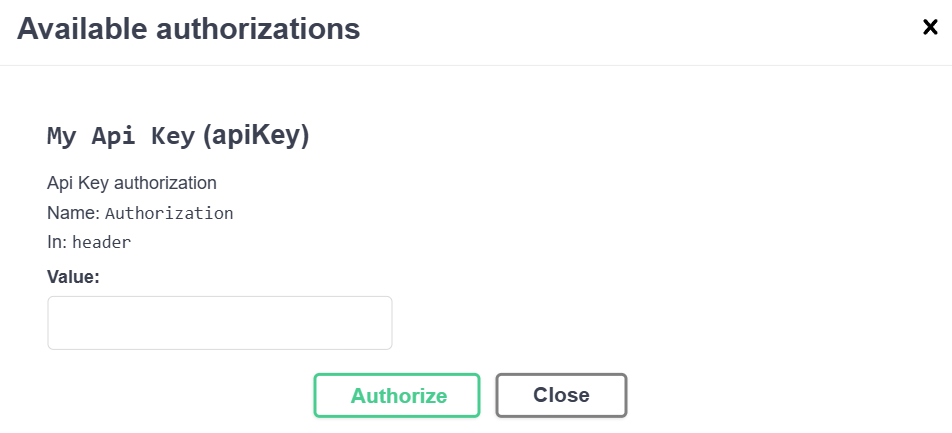

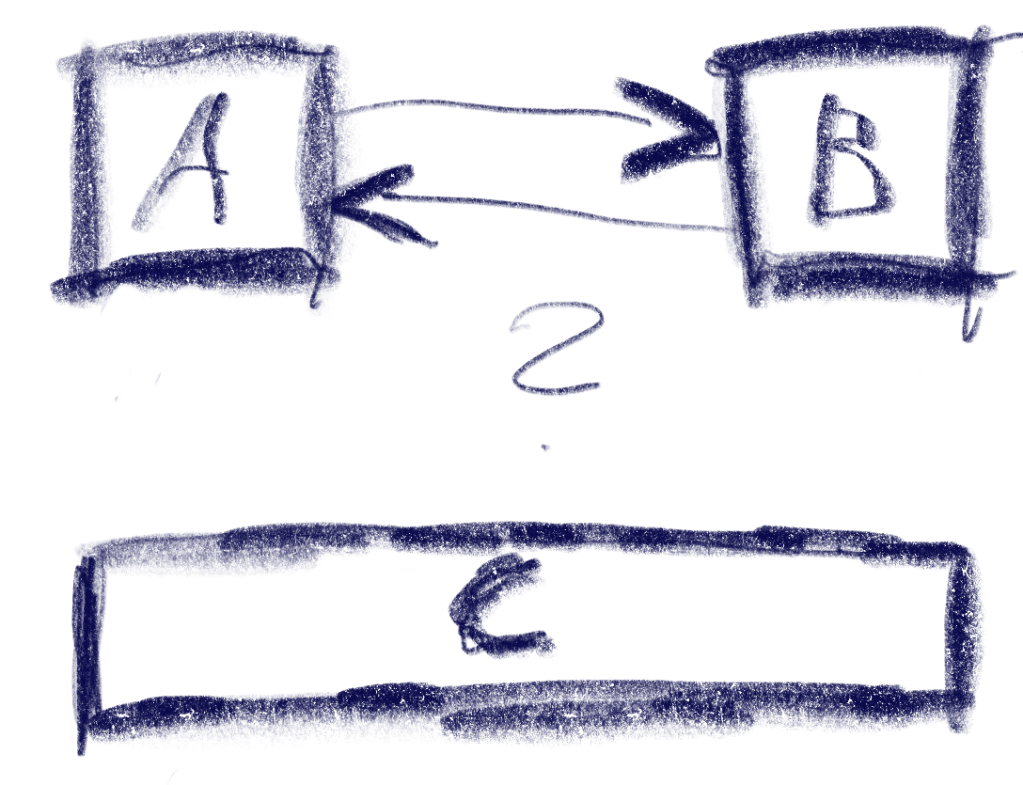

As usual, this was a multi-layered problem. It took me a while to find my optimum-for-now solution, but I think I managed, so let me try to break it down a bit. Consider the basic structure:

<ItemsControl ItemsSource="{Binding ListOfChildren}">

<ItemsControl.ItemTemplate>

<DataTemplate>

<Button Style="{StaticResource FancyButton}"

Command="{Binding SomeAwesomeCommand}"

Content="{Binding Title}"

/>

</DataTemplate>

</ItemsControl.ItemTemplate>

</ItemsControl>

Quick Note about the Style

We see the Styling of FancyButton (defined in some ResourceDictionary, merged together with a lot of stuff in the App.xaml Applications.Resources), and I want to define the styling here in order to modify it in some other places i.e. this could be defined in said ResourceDictionary like

<Style TargetType="{x:Type Button}" x:Key="FancyButton"> ... </Style>

<Style TargetType="{x:Type Button}" BasedOn="{StaticResource FancyButton}" x:Key="SmallFancyButton"> ... </Style>

<Style TargetType="{x:Type Button}" BasedOn="{StaticResource FancyButton}" x:Key="FancyAlertButton"> ... </Style>

... as you wish ...

Quick Note about the Command

We also see SomeAwesomeCommand, defined in the view model of what ListOfChildren actually consists of. So, SomeAwesomeCommand is a Property of a custom ICommand-implementing class, but there’s a catch:

Commands on a Button work on the Click event. There’s no native way to assign that to different events like e.g. DragOver, so this sounds like our new User Control would need quite some Code Behind in order to wire up any Non-Click-Event with that Command. Thankfully, there is a surprisingly simple solution, called Interaction.Triggers. Apply it as

- installing System.Windows.Interactivity from NuGet

- adding the to your XAML namespaces:

xmlns:i="clr-namespace:System.Windows.Interactivity;assembly=System.Windows.Interactivity" - Adding the trigger inside:

<Button ...>

<i:Interaction.Triggers>

<i:EventTrigger EventName="DragOver">

<i:InvokeCommandAction Command="WhateverYouFeelLike"/>

</i:EventTrigger>

</i:Interaction.Triggers>

</Button>

But that only as a side note, remember that the point of having our separate User Control is still valid; considering that you would want to have some extra interactivity in your own use cases.

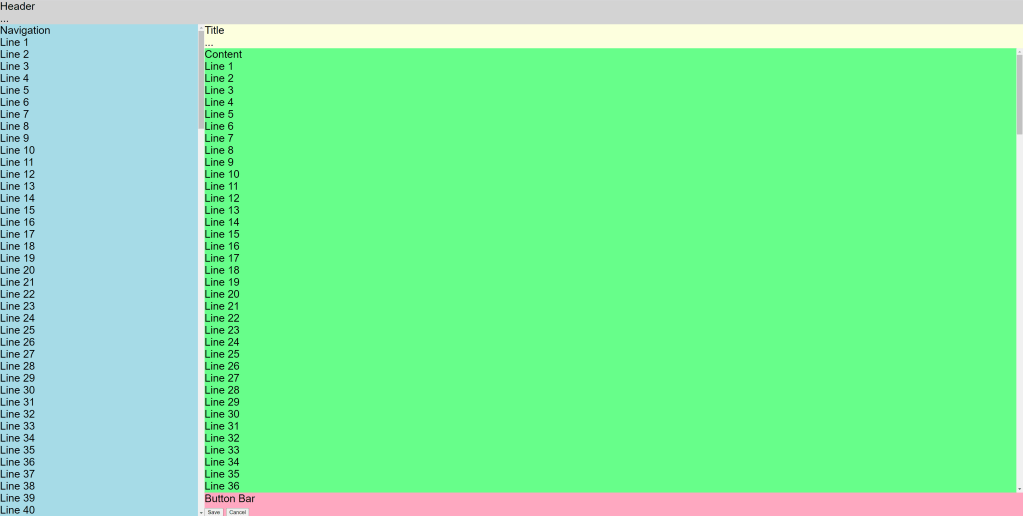

Now: Extracting the functionality to our own User Control

I chose not to derive some class from the Button class itself because it would couple me closer to the internal workings of Button; i.e. an application of Composition over Inheritance. So the first step looks easy: Right click in the VS Solution Explorer -> Add -> User Control (WPF) -> Create under some name (say, MightyButton) -> Move the <Button.../> there -> include the XAML namespace and place the MightyButton in our old code:

// old place

<Window ...

xmlns:ui="clr-namespace:WhereYourMightyButtonLives

>

...

<ItemsControl ItemsSource="{Binding ListOfChildren}">

<ItemsControl.ItemTemplate>

<DataTemplate>

<ui:MightyButton Command="{Binding SomeAwesomeCommand}"

Content="{Binding Title}"

/>

</DataTemplate>

</ItemsControl.ItemTemplate>

</ItemsControl>

...

</Window>

// MightyButton.xaml

<UserControl ...>

<Button Style="{StaticResource FancyButton}"/>

</UserControl>

But now it get’s tricky. This could compile, but still not work because of several Binding mismatches.

I’ve written a lot already, so let me just define the main problems. I want my call to look like

<ui:DropTargetButton Style="{StaticResource FancyButton}"

Command="{Binding OnBranchFolderSelect}"

...

/>

But again, these are two parts. Let me clarify.

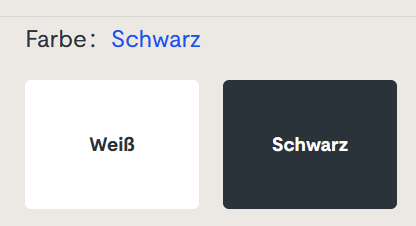

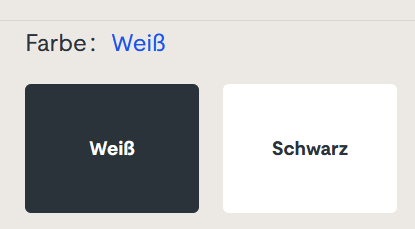

Side Quest: I want the Style to be applied from outside.

Remember the idea of having SmallFancyButton, FancyAlertButton or whatsoever? The problem is, that I can’t just pass it to <ui:MightyButton.../> as intended (see last code block), because FancyButton has its definition of TargetType="{x:Type Button}". Not TargetType="{x:Type ui:MightyButton}".

Surely I could change that. But I will regret this when I change my component again; I would always have to adjust the FancyButton definition every time (at several places) even though it always describes a Button.

So let’s keep the Style TargetType to be Button, and just treat the Style as something to be passed to the inner-lying Button.

Main Quest: Passing through Properties from the ListOfChildren members

Remember that any WPF Control inherits a lot of Properties (like Style, Margin, Height, …) from its ancestors like FrameworkElement, and you can always extend that with custom Dependency Properties. Know that Command actually is not one of these inherited Properties – it only exists for several UI Elements like the Button, but not in a general sense, so we can easily extend this.

Go to the Code Behind, and at some suitable place make a new Dependency Property. There is a Visual Studio shorthand of writing “propdp” and pressing Tab twice. Then adjust it to read like

public ICommand Command

{

get { return (ICommand)GetValue(CommandProperty); }

set { SetValue(CommandProperty, value); }

}

public static readonly DependencyProperty CommandProperty =

DependencyProperty.Register("Command", typeof(ICommand), typeof(DropTargetButton), new PropertyMetadata(null));

With Style, we have one of these inherited Properties. Nevertheless, I want my Property to be called Style, which is quite straightforward by just employing the new keyword (i.e. we really want to shadow the inherited property, which is tolerable because we already know our FancyButton Style to its full extent.)

public new Style Style

{

get { return (Style)GetValue(StyleProperty); }

set { SetValue(StyleProperty, value); }

}

public static readonly new DependencyProperty StyleProperty =

DependencyProperty.Register("Style", typeof(Style), typeof(DropTargetButton), new PropertyMetadata(null));

And then we’re nearly there, we just have to make the Button inside know where to take these Properties. In an easy setting, this could be accomplished by making the UserControl constructor set DataContext = this; but STOP!

If you do that, you lose easy access to the outer ItemsControl elements. Sure you could work around – remember the WPF philosophy of allowing you many ways – but more practicable imo is to have an ElementName. Let’s be boring and take “Root”.

<UserControl x:Class="ComplianceManagementTool.UI.DropTargetButton"

...

xmlns:i="clr-namespace:System.Windows.Interactivity;assembly=System.Windows.Interactivity"

xmlns:local="clr-namespace:ComplianceManagementTool.UI"

x:Name="Root"

>

<Button Style="{Binding Style, ElementName=Root}"

AllowDrop="True"

Command="{Binding Command, ElementName=Root}"

Content="{Binding Text, ElementName=Root}"

>

<i:Interaction.Triggers>

<i:EventTrigger EventName="DragOver">

<i:InvokeCommandAction Command="{Binding Command, ElementName=Root}"/>

</i:EventTrigger>

</i:Interaction.Triggers>

</Button>

</UserControl>

As some homework, I’ve left you the Content property to add as a Dependency Property, as well. You could go ahead and add as many DPs to your User Control, and inside that Control (which is quite maiden-like still, if we ignore all that DP boilerplate code) you could have as many complex interactivity as you would require, without losing the flexibility of passing the corresponding Commands from the outside.

Of course, this is just one way of about seventeen plusminus thirtythree, add one or two, which is about the usual number of WPF ways of doing things. Nevertheless, this solution now lives in our blog, and maybe it is of some help to you. Or Future-Me.