Docker has become one of the go-to tools of many developers these days. Not because any project should implement as many technological buzz words per se, but due to their great deal of flexibility compared with their small hassle of setup.

For stuff like node-based applications, using a Dev Container is useful because in principle, you do not need to have any of the npm stuff on your actual machine – not only you avoid having these monstrous node_modules folders, but also avoid having accidental dependencies on some specific configuration that might hold true on your device, but not generally.

For some of these reasons probably, JetBrains included Docker Dev Containers as a kind of “remote” development. In a sense, a docker container can be thought of as a remote machine, regardless of the fact that it shares your local hardware and is just a software abstraction.

In my opinion, JetBrains usually does great software, but there is some weird behaviour in their usage of Docker Dev Containers and it took us a while to find a quite general and IDE-independent solution; I’ll just use WebStorm as an example of something that appeared unusually hard to tame. I guess it will become better eventually.

For now, one might think of using the built-in config like:

- New Run Configuration -> npm

- Node Interpreter: “…”

- “+” -> Add Remote… -> “Docker”

- Use an image of your choice, either one of the node base images or a custom one (see below) with its corresponding tag

Now for reasons that seem to be completely undocumented and unavoidable (tell me if you know more!), the IDE forces you to then mount your project to /opt/project inside this container, where it gets mirrored during runtime to somewhere /tmp/<temporary uuid>/ – and in several of our projects (due to our folder structure which is not even particularly abnormal) this made this option to be completely unusable.

The way one can work without these strange idiosyncrasies is as follows:

First, create a Dockerfile in which you do all the required setup. It might be an optional idea to set the user, away from “root” to something more restricted like “node” (even though in development, you probably have your eyes on everything nevertheless). You can do more custom setup here. This can look like

FROM node:16.18.0-bullseye-slim

WORKDIR /your-home-inside-container

RUN chown node .

COPY package.json package-lock.json /your-home-inside-container

USER node

RUN npm ci --ignore-scripts

# COPY <whatever you might want> <where you want it inside>

EXPOSE 3000

CMD npm start

From that Dockerfile, build a local image in the same folder like:

# you might need -f if the Dockerfile is not named "Dockerfile"

docker build -t your-dev-image .

Then, create a new Run Configuration but choose “Shell script” (not npm)

docker run -it --rm --entrypoint= -v ${PWD}/src:/your-home-inside-container/src -p 0.0.0.0:3000:3000 your-dev-image

You might use a different “-p” port forwarding if you do not want to have your development server broadcasting on port 3000 (another advantage of Dev Containers, you can easily run multiple instances on different ports).

This is about the whole magic. But there are two further things that could be important here:

Hot Reloading (live updating whenever source files change)

This is done rather easily, however seems to change once in a while. We figured out that at least if you are using react-scripts@5.0.1 (which is what “npm start” addresses, unless you do that differently), you just need to set the environment variable “WATCHPACK_POLLING=true”. I.e put that in your Dockerfile a

ENV WATCHPACK_POLLING true

or pass it into your docker run ... -e WATCHPACK_POLLING=true ... your-dev-image line

Routing a development proxy to some “local host”

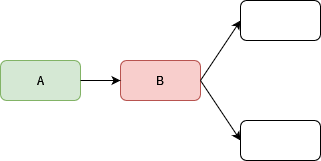

If your software e.g. adresses a backend that is running on your development machine or another Docker Dev Container, it can not just access that host from inside the Docker container. Neither is the port forwarding via “-p …:…” of any use, because that addresses the other direction – i.e. what port from the container is exposed to outside access – here, we go the other direction.

When the software inside the container would actually want to address “localhost”, it needs to be directed at the host under which your local machine appears. Docker has a special hostname for that and it is host.docker.internal

I.e. if your local backend is running on “localhost:8080” on your machine, you need to tell your Dev Container to direct its requests to “host.docker.internal:8080”.

In one of our projects, we needed some specific control over the proxy that the React development server gives you and here is way to gain that control – add a “setupProxy.js” inside your src/ folder and put in it something like

const { createProxyMiddleware } = require('http-proxy-middleware');

module.exports = function(app) {

if (process.env.LOCAL_DEVELOPMENT) {

return;

}

let httpProxyMiddleware = createProxyMiddleware({

target: process.env.REACT_APP_PROXY || 'http://localhost:8080',

changeOrigin: true,

});

app.use('/api', httpProxyMiddleware); // change to your needs accordingly

};

This way, one can always change the address via setting a REACT_APP_PROXY environment variable as in the step above; and one can also disable the whole proxying by setting the LOCAL_DEVELOPMENT env variable to true. Name these as you like, and you can even extend this setupProxy to include web sockets or different proxies for different routes, if you have any questions on that, just comment below 🙂