If you couldn’t attend the Schneide Dev Brunch at 14th of August 2016, here is a summary of the main topics.

Two weeks ago at sunday, we held another Schneide Dev Brunch, a regular brunch on the second sunday of every other (even) month, only that all attendees want to talk about software development and various other topics. This brunch had its first half on the sun roof of our company, but it got so sunny that we couldn’t view a presentation that one of our attendees had prepared and we went inside. As usual, the main theme was that if you bring a software-related topic along with your food, everyone has something to share. We were quite a lot of developers this time, so we had enough stuff to talk about. As usual, a lot of topics and chatter were exchanged. This recapitulation tries to highlight the main topics of the brunch, but cannot reiterate everything that was spoken. If you were there, you probably find this list inconclusive:

Two weeks ago at sunday, we held another Schneide Dev Brunch, a regular brunch on the second sunday of every other (even) month, only that all attendees want to talk about software development and various other topics. This brunch had its first half on the sun roof of our company, but it got so sunny that we couldn’t view a presentation that one of our attendees had prepared and we went inside. As usual, the main theme was that if you bring a software-related topic along with your food, everyone has something to share. We were quite a lot of developers this time, so we had enough stuff to talk about. As usual, a lot of topics and chatter were exchanged. This recapitulation tries to highlight the main topics of the brunch, but cannot reiterate everything that was spoken. If you were there, you probably find this list inconclusive:

Open-Space offices

There are some new office buildings in town that feature the classic open-space office plan in combination with modern features like room-wide active noise cancellation. In theory, you still see your 40 to 50 collegues, but you don’t necessarily hear them. You don’t have walls and a door around you but are still separated by modern technology. In practice, that doesn’t work. The noise cancellation induces a faint cheeping in the background that causes headaches. The noise isn’t cancelled completely, especially those attention-grabbing one-sided telephone calls get through. Without noise cancellation, the room or hall is way too noisy and feels like working in a subway station.

We discussed how something like this can happen in 2016, with years and years of empirical experience with work settings. The simple truth: Everybody has individual preferences, there is no golden rule. The simple conclusion would be to provide everybody with their preferred work environment. Office plans like the combi office or the flexspace office try to provide exactly that.

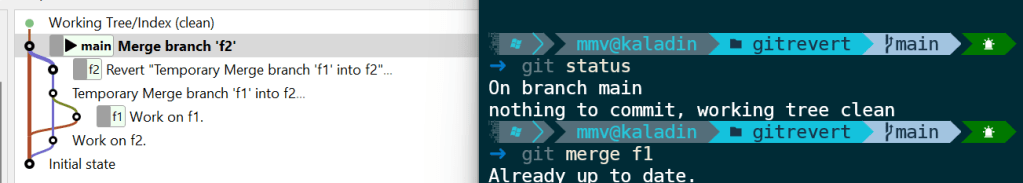

Retrospective on the Git internal presentation

One of our attendees gave a conference talk about the internals of git, and sure enough, the first question of the audience was: If git relies exclusively on SHA-1 hashes and two hashes collide in the same repository, what happens? The first answer doesn’t impress any analytical mind based on logic: It’s so incredibly improbable for two SHA-1 hashes to collide that you might rather prepare yourself for the attack of wolves and lightning at the same time, because it’s more likely. But what if it happens regardless? Well, one man went out and explored the consequences. The sad result: It depends. It depends on which two git elements collide in which order. The consequences range from invisible warnings without action over silently progressing repository decay to immediate data self-destruction. The consequences are so bitter that we already researched about the savageness of the local wolve population and keep an eye on the thunderstorm app.

Helpful and funny tools

A part of our chatter contained information about new or noteworthy tools to make software development more fun. One tool is the elastic tabstop project by Nick Gravgaard. Another, maybe less helpful but more entertaining tool is the lolcommits app that takes a mugshot – oh sorry, we call that “aided selfie” now – everytime you commit code. That smug smile when you just wrote your most clever code ever? It will haunt you during a git blame session two years later while trying to find that nasty heisenbug.

Anonymous internet communication

We invested a lot of time on a topic that I will only decribe in broad terms. We discussed possibilities to communicate anonymously over a compromised network. It is possible to send hidden messages from A to B using encryption and steganography, but a compromised network will still be able to determine that a communication has occured between A and B. In order to communicate anonymously, the network must not be able to determine if a communication between A and B has happened or not, regardless of the content.

A promising approach was presented and discussed, with lots of references to existing projects like https://github.com/cjdelisle/cjdns and https://hyperboria.net/. The usual suspects like the TOR project were examined as well, but couldn’t hold up to our requirements. At last, we wanted to know how hard it is to found a new internet service provider (ISP). It’s surprisingly simple and well-documented.

Web technology to single you out

We ended our brunch with a rather grim inspection about the possibilities to identify and track every single user in the internet. To use completely exotic means of surfing is not helpful, as explained in this xkcd comic. When using a stock browser to surf, your best practice should be to not change the initial browser window size – but just see for yourself if you think it makes a difference. Here is everything What Web Can Do Today to identify and track you. It’s so extensive, it’s really scary, but on the other hand quite useful if you happen to develop a “good” app on the web.

Epilogue

As usual, the Dev Brunch contained a lot more chatter and talk than listed here. The number of attendees makes for an unique experience every time. We are looking forward to the next Dev Brunch at the Softwareschneiderei. And as always, we are open for guests and future regulars. Just drop us a notice and we’ll invite you over next time.

For the gamers: Schneide Game Nights

Another ongoing series of events that we established at Softwareschneiderei are the Schneide Game Nights that take place at an irregular schedule. Each Schneide Game Night is a saturday night dedicated to a new or unknown computer game that is presented by a volunteer moderator. The moderator introduces the guests to the game, walks them through the initial impressions and explains the game mechanics. If suitable, the moderator plays a certain amount of time to show more advanced game concepts and gives hints and tipps without spoiling too much suprises. Then it’s up to the audience to take turns while trying the single player game or to fire up the notebooks and join a multiplayer session.

We already had Game Nights for the following games:

- Kerbal Space Program: A simulator for everyone who thinks that space travel surely isn’t rocket science.

- Dwarf Fortress: A simulator for everyone who is in danger to grow attached to legendary ASCII socks (if that doesn’t make much sense now, lets try: A simulator for everyone who loves to dig his own grave).

- Minecraft: A simulator for everyone who never grew out of the LEGO phase and is still scared in the dark. Also, the floor is lava.

- TIS-100: A simulator (sort of) for everyone who thinks programming in Assembler is fun. Might soon be an olympic discipline.

- Faster Than Light: A roguelike for everyone who wants more space combat action than Kerbal Space Program can provide and nearly as much text as in Dwarf Fortress.

- Don’t Starve: A brutal survival game in a cute comic style for everyone who isn’t scared in the dark and likes to hunt Gobblers.

- Papers, Please: A brutal survival game about a bureaucratic hero in his border guard booth. Avoid if you like to follow the rules.

- This War of Mine: A brutal survival game about civilians in a warzone, trying not to simultaneously lose their lives and humanity.

- Crypt of the Necrodancer: A roguelike for everyone who wants to literally play the vibes, trying to defeat hordes of monsters without skipping a beat.

- Undertale: A 8-bit adventure for everyone who fancies silly jokes and weird storytelling. You’ll feel at home if you’ve played the NES.

The Schneide Game Nights are scheduled over the same mailing list as the Dev Brunches and feature the traditional pizza break with nearly as much chatter as the brunches. The next Game Night will be about:

- Factorio: A simulator that puts automation first. Massive automation. Like, don’t even think about doing something yourself, let the robots do it a million times for you.

If you are interested in joining, let us know.