In the first part of this series, I talked about describing unit tests with the metaphor of a stage play that tells short stories about your system.

This metaphor holds its water in nearly every aspect of unit testing and guides my approach from each single line of code to the whole concept of test coverage. In this series, I’m focussing on one aspect in each part.

Today, we look at the backdrop.

We learnt from the first part that most unit tests are performed by four roles that appear on stage. In a theater, the stage is oftentimes decorated by additional items that facilitate the story. This is the backdrop (or the coulisse) of the play. We have the same thing in unit tests.

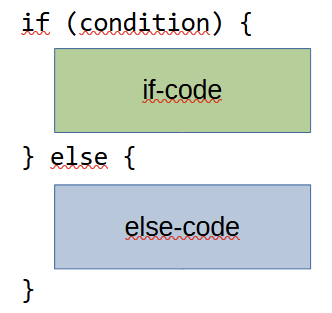

In a unit test, the stage is the code inside the test method:

@Test

public void rounds_up_to_the_next_decimal_power() {

final Configuration given = new Configuration(

StringVirtualFile.createFileFromContent(

"report.config",

"scale.maximum=2E5"

)

);

final ReportConfiguration target = new ReportConfiguration(

given

SuffixProvider.none

);

final Optional<Double> actual = target.scaleMaximum();

final double expected = 1E6;

assertThat(actual).contains(expected);

}A good director is very picky about every detail that appears on stage. There should be no incidental item visible for the audience. In the case of an unit test, the audience is the next developer that reads the test code.

The stage doesn’t need to be devoid of “extras” and furniture, but it should be limited to the essential. A theater play isn’t a movie set where eye candy is seen as something positive. During the play, the audience should recognize the actors (and their roles) easily and without searching between all the clutter.

So we need to do two things: Declutter the stage and identify the extras.

Decluttering the stage

In our example above, there is a mismatch between the code required to instantiate the given role and the rest of the whole test. If this were a real play, half the time would be spent on an extra that doesn’t even speak a line. It is implied that the target gets some information from the given, but it isn’t shown. We need to remove some details from the stage that aren’t even relevant to the story, but introduced in detail just like the essential things. It might be fun and suspenseful to guess if the “report.config” detail in line three is more meaningful than the “scale.maximum” specified in line four, but unit test stories are not meant to be mysterious or even entertaining. They are meant to inform the audience about a little fact of the tested system. There will be thousands of little stories about the system. Make them trivial to read and easy to understand.

We need to move the stage props off the stage:

@Test

void rounds_up_to_the_next_decimal_power() {

Configuration given = givenScaleMaximumOf("2E5");

final ReportConfiguration target = new ReportConfiguration(

given,

irrelevant()

);

final Optional<Double> actual = target.scaleMaximum();

final double expected = 1E6;

assertThat(actual).contains(expected);

}

private Configuration givenScaleMaximumOf(

String scaleMaximum

) {

return new Configuration(

StringVirtualFile.createFileFromContent(

"report.config",

"scale.maximum=" + scaleMaximum

)

);

}

private SuffixProvider irrelevant() {

return SuffixProvider.none;

}By moving the initialization code of the Configuration object to a new private method, we employ the storytelling device of “conveniently prepared circumstances”. The private method is moved to the “lower decks” or the “backstage” area of our test class. “The stage is on top” might be our motto. Everything “private” or not-Test-annotated should not be visible first and should not be required reading.

Notice how I introduced a parameter to the new “givenScaleMaximumOf” method in order to keep the necessary test details on stage. The audience should not have to look behind the curtains to gather important information about the story. I made the parameter a string (and not a double or integer) because it is just a prop. The story doesn’t benefit from it being typecasted correctly. And if you look back, it was a string before, too.

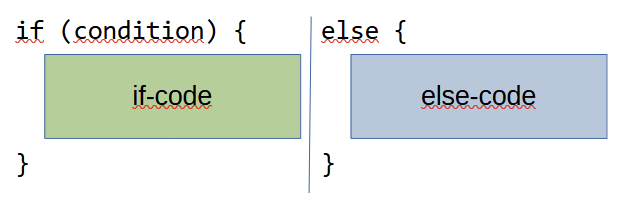

Identifying the extras

I’ve also extracted the “magic number” or “silent extra” SuffixProvider.none into its own method. This method adds nothing but a name that conveys the meaning of the value to the story instead of the value itself. If I were a directory in a theater, this actor would have a plain and bland costume in contrast to the bright colored main roles. Maybe the stage lighting would illuminate the main roles and keep the extra in the shadowy area, too.

Now, the focus of our test method is back on the main story. The attention of our audience will be on the stage and it will not be burdened by irrelevant details. We will even label props as dispensable if they are.

Keep your stages free from clutter and the eyes of your audience on the story. Test code is boring by nature. It doesn’t have to be plodding, too.

Epilogue

This is the second part of a series. All parts are linked below: