In the first and second parts of this series, I talked about describing unit tests with the metaphor of a stage play that tells short stories about your system.

This metaphor is really useful in many aspects of unit testing, as we have seen with naming variables and clearing the test method. In each blog entry of the series, I’m focussing on one aspect of the whole.

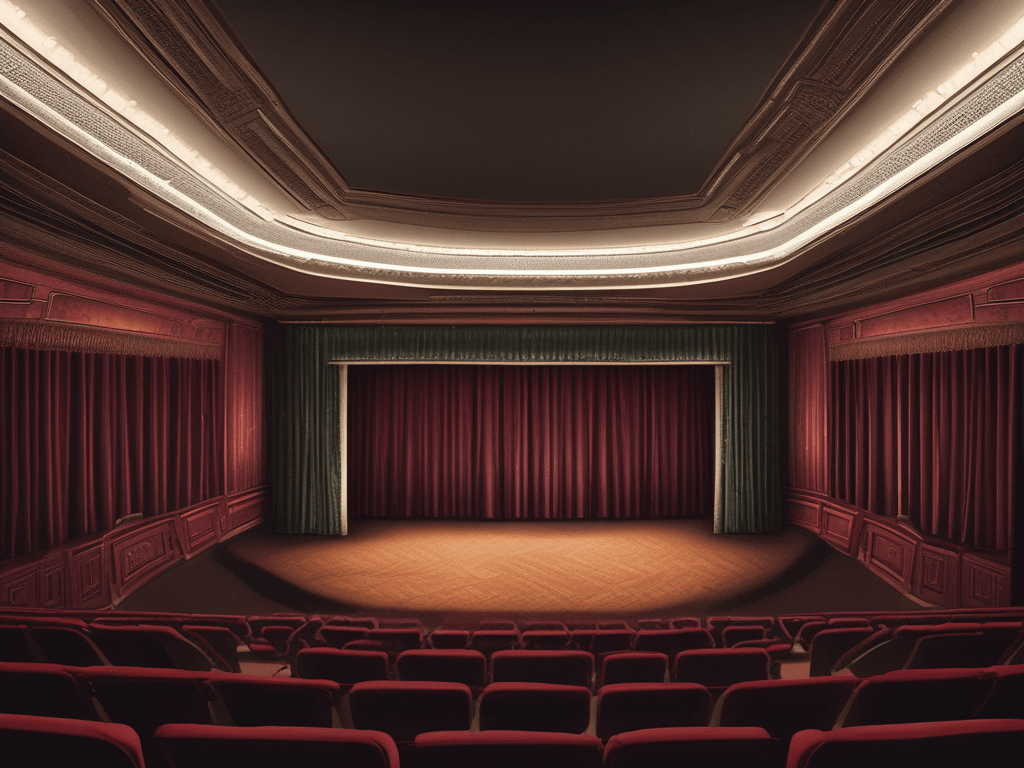

Today, we look at the theater.

If you go to the theater as a guest, you are greeted by a pompous entrance with a luxurious stairway that lead you to your comfy seat. You don’t get to see all the people and things behind the heavy curtains. You don’t need to recognize any details of the floor, the walls or the ceiling as you make your way into the auditorium. They don’t matter for the play.

If you enter the theater as an actor or a stage help, you slip into the building by the back entrance and make your way through a series of storage rooms. Or at least that is the cliché in many movies (I’m thinking about Birdman, but you probably have your own mental image at hands). You need to recognize all the details and position yourself according to your job. Your preparation matters for the play.

I described the test methods as single stage plays in earlier blog posts. Today, I want you to think about a test class as a theater. We need to agree on the position of the entrance. In my opinion, the entrance is where I’m starting to read – at the top of the file.

In my opinion, as a reader of the test class, I’m one of the guests. My expectation is that the test class is designed to be inviting to guests.

This expectation comes from a fundamental difference between production code classes and test classes: Classes in production code are not meant to be read. In fact, if you tailor your modules right and design the interface of a class clearly and without surprises, I want to utilize your class, but don’t read it. I don’t have to read it because the interface told me everything I needed to know about your class. Spare me the details, I’ve got problems to solve!

Test classes, on the other hand, are meant to be read. Nobody will call a test method from the production code. The interface of a test class is confusing from the outside. To value a test class is to read and understand it.

Production code classes are like goverment agencies: They serve you at the front, but don’t want you to snoop around the internals. Test classes are like a theater: You are invited to come inside and marvel at the show.

So we should design our test classes like theaters: An inviting upper part for the guests and a pragmatic lower part for the stage hands behind the curtain.

Let’s look at an example:

public class UninvitingTest {

public static class TestResult {

private final PulseCount[] counts;

private final byte[] bytes;

public TestResult(

final PulseCount count,

final byte[] bytes

) {

this(

new PulseCount[] {

count

},

bytes

);

}

public TestResult(

final PulseCount[] counts,

final byte[] bytes

) {

super();

this.counts = counts;

this.bytes = bytes;

}

public PulseCount[] getCounts() {

return this.counts;

}

public byte[] getBytes() {

return this.bytes;

}

}

private static final TestResult ZERO_COUNT =

new TestResult(

new PulseCount(0),

new byte[] {0x0, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0}

);

private static final TestResult VERY_SMALL_COUNT =

new TestResult(

new PulseCount(34),

new byte[] {0x0, 0x0, 0x22, 0x0}

);

private static final TestResult MEDIUM_COUNT_BORDER =

new TestResult(

new PulseCount(65536),

new byte[] {0x1, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0}

);

public UninvitingTest() {

super();

}

@Test

public void serializeSingleChannelValues() throws Exception {

SPEChannelValuesSerializer scv =

new SPEChannelValuesSerializer();

Assertion.assertArrayEquals(

ZERO_COUNT.getBytes(),

scv.serializeCounts(ZERO_COUNT.getCounts())

);

Assertion.assertArrayEquals(

VERY_SMALL_COUNT.getBytes(),

scv.serializeCounts(VERY_SMALL_COUNT.getCounts())

);

Assertion.assertArrayEquals(

MEDIUM_COUNT_BORDER.getBytes(),

scv.serializeCounts(MEDIUM_COUNT_BORDER.getCounts())

);

}

}In fact, I hope you didn’t read the whole thing. There are lots of problems with this test, but let’s focus on the entrance part:

- Package declaration (omitted here)

- Import statements (omitted here)

- Class declaration

- Inner class definition

- Constant definitions

- Constructor

- Test method

The amount depends on the programming language, but some ornaments at the top of a file are probably required and can’t be skipped or moved around. We can think of them as a parking lot that we require, but don’t find visually appealing.

The class declaration is something like an entrance door. Behind it, the theater begins. And just by looking at the next three things, I can tell that I took the wrong door. Why am I burdened with the implementation details of a whole other class? Do I need to remember any of that? Are the constants important? Why does a test class require a constructor?

In this test class, I need to travel 50 lines of code before I reach the first test method. Translated into our metaphor, this would be equivalent to three storage rooms filled with random stuff that I need to traverse before I can sit into my chair to watch the play. It would be ridiculous when encountered in real life.

The solution isn’t that hard: Store your stuff in the back rooms. We just need to move our test method up, right under the class declaration. Everything else is defined at the bottom of our class, after the test methods.

This is a clear violation of the Java code conventions and the usual structure of a class. Just remember this: The code conventions and structures apply to production code and are probably useful for it. But we have other requirements for our test classes. We don’t need to know about the intrinsic details of that inner class because it will only be used in a few test methods. The constants aren’t public and won’t just change. The only call to our constructor lies outside of our code in the test framework. We don’t need it at all and should remove it.

If you view your test class as a theater, you store your stuff in the back and present an inviting front to your readers. You know why they visit you: They want to read the tests, so show them the tests as proximate as possible. Let the compiler travel your code, not your readers.

And just so show you the effect, here is the nasty test class from above, with the more inviting structure:

public class UninvitingTest {

@Test

public void serializeSingleChannelValues() throws Exception {

SPEChannelValuesSerializer scv =

new SPEChannelValuesSerializer();

Assertion.assertArrayEquals(

ZERO_COUNT.getBytes(),

scv.serializeCounts(ZERO_COUNT.getCounts())

);

Assertion.assertArrayEquals(

VERY_SMALL_COUNT.getBytes(),

scv.serializeCounts(VERY_SMALL_COUNT.getCounts())

);

Assertion.assertArrayEquals(

MEDIUM_COUNT_BORDER.getBytes(),

scv.serializeCounts(MEDIUM_COUNT_BORDER.getCounts())

);

}

private static final TestResult ZERO_COUNT =

new TestResult(

new PulseCount(0),

new byte[] {0x0, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0}

);

private static final TestResult VERY_SMALL_COUNT =

new TestResult(

new PulseCount(34),

new byte[] {0x0, 0x0, 0x22, 0x0}

);

private static final TestResult MEDIUM_COUNT_BORDER =

new TestResult(

new PulseCount(65536),

new byte[] {0x1, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0}

);

public static class TestResult {

private final PulseCount[] counts;

private final byte[] bytes;

public TestResult(

final PulseCount count,

final byte[] bytes

) {

this(

new PulseCount[] {

count

},

bytes

);

}

public TestResult(

final PulseCount[] counts,

final byte[] bytes

) {

super();

this.counts = counts;

this.bytes = bytes;

}

public PulseCount[] getCounts() {

return this.counts;

}

public byte[] getBytes() {

return this.bytes;

}

}

public UninvitingTest() {

super();

}

}Show your readers the test methods and don’t burden them with details they just don’t need (yet).

Epilogue

This is the third part of a series. All parts are linked below:

- Part I: The actors

- Part II: The backdrop

- Part III: The theater (you are right here in the middle!)

- Part IV: The story

- Part V: The critics