Last week, I had a really annoying error in one of our React-Redux applications. It started with a believed-to-be-minor cleanup in our code, culminated in four developers staring at our code in disbelief and quite some research, and resulted in some rather feasible solutions that, in hindsight, look quite obvious (as is usually the case).

The tech landscape we are talking about here is a React webapp that employs state management via Redux-Toolkit / RTK, the abstraction layer above Redux to simplify the majority of standard use cases one has to deal with in current-day applications. Personally, I happen to find that useful, because it means a perceptible reduction of boilerplate Redux code (and some dependencies that you would use all the time anyway, like redux-thunk) while maintaining compatibility with the really useful Redux DevTools, and not requiring many new concepts. As our application makes good use of URL routing in order to display very different subparts, we implemented our own middleware that does the data fetching upfront in a major step (sometimes called „hydration“).

One of the basic ideas in Redux-Toolkit is the management of your state in substates called slices that aim to unify the handling of actions, action creators and reducers, essentially what was previously described as Ducks pattern.

We provide unit tests with the jest framework, and generally speaking, it is more productive to test general logic instead of React components or Redux state updates (although we sometimes make use of that, too). Jest is very modular in the sense that you can add tests for any JavaScript function from whereever in your testing codebase, the only thing, of course, is that these functions need to be exported from their respective files. This means that a single jest test only needs to resolve the imports that it depends on, recursively (i.e. the depenency tree), not the full application.

Now my case was as follows: I wrote a test that essentially was just testing a small switch/case decision function. I noticed there was something fishy when this test resulted in errors of the kind

- Target container is not a DOM element. (pointing to ReactDOM.render)

- No reducer provided for key “user” (pointing to node_modules redux/lib/redux.js)

- Store does not have a valid reducer. Make sure the argument passed to combineReducers is an object whose values are reducers. (also …/redux.js)

This meant there was too much going on. My unit test should neither know of React nor Redux, and as the culprit, I found that one of the imports in the test file used another import that marginally depended on a slice definition, i.e.

///////////////////////////////

// test.js

///////////////////////////////

import {helper} from "./Helpers.js"

...

///////////////////////////////

// Helpers.js

///////////////////////////////

import {SOME_CONSTANT} from "./state/generalSlice.js"

...

Now I only needed some constant located in generalSlice, so one could easily move this to some “./const.js”. Or so I thought.

When I removed the generalSlice.js depency from Helpers.js, the React application broke. That is, in a place totally unrelated:

ReferenceError: can't access lexical declaration 'loadPage' before initialization

./src/state/loadPage.js/</<

http:/.../static/js/main.chunk.js:11198:100

./src/state/topicSlice.js/<

C:/.../src/state/topicSlice.js:140

> [loadPage.pending]: (state, action) => {...}

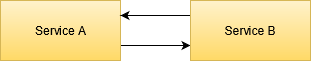

From my past failures, I instantly recalled: This is a problem with circular dependencies.

Alas, topicSlice.js imports loadPage.js and loadPage.js imports topicSlice.js, and while some cases allow such a circle to be handled by webpack or similar bundlers, in general, such import loops can cause problems. And while I knew that before, this case was just difficult for me, because of the very nature of RTK.

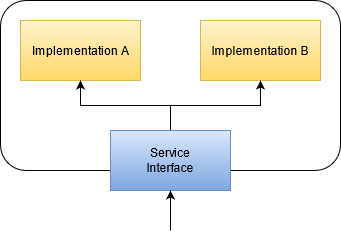

So this is a thing with the RTK way of organizing files:

- Every action that clearly belongs to one specific slice, can directly be defined in this state file as a property of the “reducers” in createSlice().

- Every action that is shared across files or consumed in more than one reducer (in more than one slice), can be defined as one of the “extraReducers” in that call.

- Async logic like our loadPage is defined in thunks via createAsyncThunk(), which gives you a place suited for data fetching etc. that always comes with three action creators like loadPage.pending, loadPage.fulfilled and loadPage.rejected

- This looks like

///////////////////////////////

// topicSlice.js

///////////////////////////////

import {loadPage} from './loadPage.js';

const topicSlice = createSlice({

name: 'topic',

initialState,

reducers: {

setTopic: (state, action) => {

state.topic= action.payload;

},

...

},

extraReducers: {

[loadPage.pending]: (state, action) => {

state.topic = initialState.topic;

},

...

});

export const { setTopic, ... } = topicSlice.actions;

And loadPage itself was a rather complex action creator (thunk), as it could cause state dispatches as well, as it was built, in simplified form, as:

///////////////////////////////

// loadPage.js

///////////////////////////////

import {setTopic} from './topicSlice.js';

export const loadPage = createAsyncThunk('loadPage', async (args, thunkAPI) => {

const response = await fetchAllOurData();

if (someCondition(response)) {

await thunkAPI.dispatch(setTopic(SOME_TOPIC));

}

return response;

};

You clearly see that import loop: loadPage needs setTopic from topicSlice.js, topicSlice needs loadPage from loadPage.js. This was rather old code that worked before, so it appeared to me that this is no problem per se – but solving that completely different dependency in Helpers.js (SOME_CONSTANT from generalSlice.js), made something break.

That was quite weird. It looked like this not-really-required import of SOME_CONSTANT made ./generalSlice.js load first, along with it a certain set of imports include some of the dependencies of either loadPage.js or topicSlice.js, so that when their dependencies would have been loaded, their was no import loop required anymore. However, it did not appear advisable to trace that fact to its core because the application has grown a bit already. We needed a solution.

As I told before, it required the brainstorming of multiple developers to find a way of dealing with this. After all, RTK appeared mature enough for me to dismiss “that thing just isn’t fully thought through yet”. Still, code-splitting is such a basic feature that one would expect some answer to that. What we did come up with was

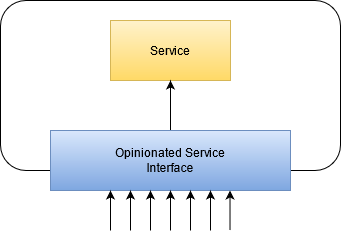

- One could address the action creators like loadPage.pending (which is created as a result of RTK’s createAsyncThunk) by their string equivalent, i.e.

["loadPage/pending"] instead of [loadPage.pending] as key in the extraReducers of topicSlice. This will be a problem if one ever renames the action from “loadPage” to whatever (and your IDE and linter can’t help you as much with errors), which could be solved by writing one’s own action name factory that can be stashed away in a file with no own imports. - One could re-think the idea that

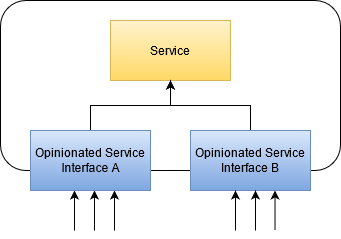

setTopic should be among the normal reducers in topicSlice, i.e. being created automatically. Instead, it can be created in its own file and then being referenced by loadPage.js and topicSlice.js in a non-circular manner as export const setTopic = createAction('setTopic'); and then you access it in extraReducers as [setTopic]: ... . - One could think hard about the construction of loadPage. This whole thing is actually a hint that loadPage does too many things on too many different levels (i.e. it violates at least the principles of Single Responsibility and Single Level of Abstraction).

- One fix would be to at least do away with the automatically created loadPage.pending / loadPage.fulfilled / loadPage.rejected actions and instead define custom

createAction("loadPage.whatever") with whatever describes your intention best, and put all these in your own file (as in idea 2). - Another fix would be splitting the parts of loadPage to other thunks, and the being able to react on the automatically created

pending / fulfilled / rejected actions each.

I chose idea 2 because it was the quickest, while allowing myself to let idea 3.1 rest a bit. I guess that next time, I should favor that because it makes the developer’s intention (as in… mine) more clear and the Redux DevTools output even more descriptive.

In case you’re still lost, my solution looks as

///////////////////////////////

// sharedTopicActions.js

///////////////////////////////

import {createAction} from "@reduxjs/toolkit";

export const setTopic = createAction('topic/set');

//...

///////////////////////////////

// topicSlice.js

///////////////////////////////

import {setTopic} from "./sharedTopicActions";

const topicSlice = createSlice({

name: 'topic',

initialState,

reducers: {

...

},

extraReducers: {

[setTopic]: (state, action) => {

state.topic= action.payload;

},

[loadPage.pending]: (state, action) => {

state.topic = initialState.topic;

},

...

});

///////////////////////////////

// loadPage.js, only change in this line:

///////////////////////////////

import {setTopic} from "./sharedTopicActions";

// ... Rest unchanged

So there’s a simple tool to break circular dependencies in more complex Redux-Toolkit slice structures. It was weird that it never occured to me before, i.e. up until to this day, I always was able to solve circular dependencies by shuffling other parts of the import.

My problem is fixed. The application works as expected and now all the tests work as they should, everything is modular enough and the required change was not of a major structural redesign. It required to think hard but had a rather simple solution. I have trust in RTK again, and one can be safe again in the assumption that JavaScript imports are at least deterministic. Although I will never do the work to analyse what it actually was with my SOME_CONSTANT import that unknowingly fixed the problem beforehand.

Is there any reason to disfavor idea 3.1, though? Feel free to comment your own thoughts on that issue 🙂