So, one of the biggest software developer joys is, when a customer, after you developed some software for them a few years back, is returning to you with change requests and it turns out that the reason you didn’t hear much from them was not complete abandonment of their project, or utter mistrust in your capabilites, or – you name it – but just that the software worked without any problems. It just did its job.

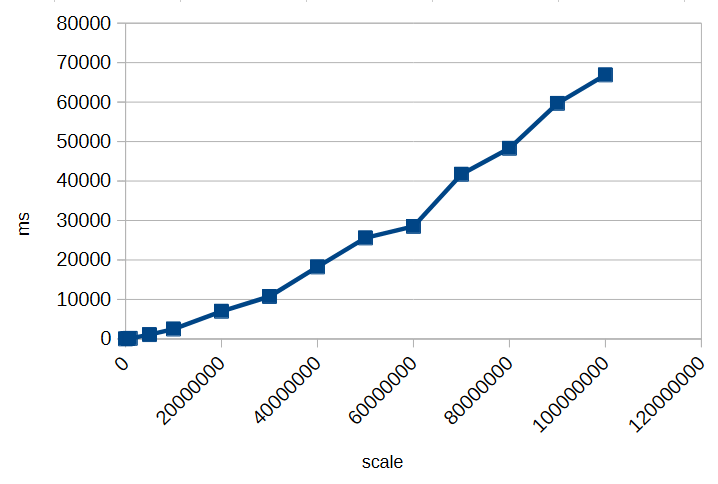

But one of the next biggest joys is, then, to actually experience how your software behaves after their staff – also just doing their job – growed their database up to a huge number of records and now you see your system under pressure, with all parts playing each other in large scales.

Now, with interactions like on-the-fly-updates during mouse gestures like drag’n’drop, falling behind real-time can be more than a minor nuisance; this might go against a core purpose of such a gesture. But how do you troubleshoot an application which is behaving smoothly most of the time, but then have very costly computations during short periods of time?

Naively, one would just put logging statements in every part that can possibly want to update, but this very quickly meets its limit when your interface just has so many components on display, and you can’t just check that one interaction on one singular part?

This is where I thought of this small device, which I now wanted to share. In my case, this was a React application, but we just use a single object, defined globally, which is modified by a single function like this

const debugBatch = {

seen: [],

since: null,

timeoutId: null

};

const logBatched = (id)=> {

if (debugBatch.timeoutId) {

debugBatch.seen.push(id);

} else {

debugBatch.since = new Date();

debugBatch.seen = [];

debugBatch.timeoutId = setTimeout(() => {

console.log("[UPDATED],", debugBatch);

debugBatch.timeoutId = null;

}, 1000);

}

};

const SomeComplicatedComponent = ({id, ...}) => {

...

logBatched(id);

return <>...</>;

};

and I do feel compelled to emphasize that this completely goes outside the React way of thinking, taking care with every state to follow the framework-internal logic. Not some global object, i.e. shared memory that any component can modify at will. But while for production code, I would hardly advise doing so, our debugging profits from that ghostly setup of “every component just raises the I-was-updated-information to somewhere out of its realm”.

It just uses one global timeout, giving a short time frame during which every repeated function call of logBatched(...); raises one entry in the “seen” field of our global object; and when that collection period is over, you get one batched output containing all the information. And you can easily extend that by passing more information along, or maybe, replacing that seen: [] with a new Set() if registering multiple updates of the same component is not what you want. (Also, the timestamp is there just out of habit, it’s not magically required or so).

Note that you can do all additional processing of “how do I need to prepare my debugging statements in order to actually see who the real culprits are” after collecting, and done in an extra task, can even be as expensive as you want it to be without blocking your rendering. As in, having debugging code that significantly affects the actual problem that you are trying to understand, is especially probable in such real-time user interactions; which means you are prone to chasing phantoms.

I like this thing because of its simplicity, and particularly, because it employs a way of thinking that would instinctively make me doubt the qualification of anyone who would give me such a piece to review (😉) but for that specific use case, I’d say, does the job pretty well.