A couple of weeks ago, I asked my brother to test out my new game You Are Circle (please wishlist it and check out the demo, if that’s up your alley!) and among lots of other valuable feedback, he mentioned that the explosion sound effects had a weird click sound at the end that he could only hear with his headphones on. For those of you not familiar with audio signal processing, those click or pop sounds usually appear when the ‘curvy’ audio signal is abruptly cut off1. I did not notice it on my setup, but he has a lot of experience with audio mixing, so I trusted his hearing. Immediately, I looked at the source files in audacity:

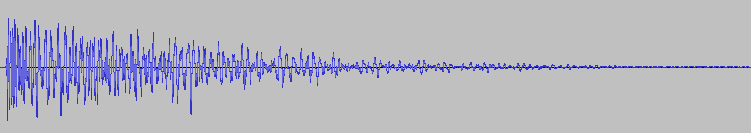

They looked fine, really. The sound slowly fades out, which is the exact thing you need to do to prevent clicks & pops. Suspecting the problem might be on the playback side of his particular setup, I asked him to record the sound on his computer the next time he tested and then kind of forgot about it for a bit.

Fast-forward a couple of days. Neither of us had followed up on the little clicky noise thing. While doing some video captures with OBS, I noticed that the sound was kind of terrible in some places, the explosions in particular. Maybe that was related?

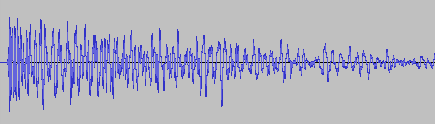

While building a new version of my game, Compiling resources... showed up in my console and it suddenly dawned on me: What if my home-brew resource compiler somehow broke the audio files? I use it to encode all the .wav originals into Ogg Vorbis for deployment. Maybe a badly configured encoding setup caused the weird audio in OBS and for my brother? So I looked at the corresponding .ogg files, and to my surprise, it indeed had a small abrupt cut-off at the end. How could that happen? Only when I put both the original and the processed file next to each other, did I see what was actually going on:

It’s only half the file! How did that happen? And what made this specific file so special for it to happen? This is one of many files that I also convert from stereo to mono in preprocessing. So I hypothesized that might be the problem. No way I missed all of those files being cut in half though, or did I? So I checked the other files that were converted from stereo to mono. Apparently, I did miss it. They were all cut in half. So I took a look at the code. It looked something like this:

while (keep_encoding)

{

auto samples_in_block = std::min(BLOCK_SIZE, input.sample_count() - sample_offset);

if (samples_in_block != 0)

{

auto samples_per_channel = samples_in_block / channel_count;

auto channel_buffer = vorbis_analysis_buffer(&dsp_state, BLOCK_SIZE);

auto input_samples = input.samples() + sample_offset;

if (convert_to_mono)

{

for (int sample = 0; sample < samples_in_block; sample += 2)

{

int sample_in_channel = sample / channel_count;

channel_buffer[0][sample_in_channel] = (input_samples[sample] + input_samples[sample + 1]) / (2.f * 32768.f);

}

}

else

{

for (int sample = 0; sample < samples_in_block; ++sample)

{

int channel = sample % channel_count;

int sample_in_channel = sample / channel_count;

channel_buffer[channel][sample_in_channel] = input_samples[sample] / 32768.f;

}

}

vorbis_analysis_wrote(&dsp_state, samples_per_channel);

sample_offset += samples_in_block;

}

else

{

vorbis_analysis_wrote(&dsp_state, 0);

}

/* more stuff to encode the block using the ogg/vorbis API... */

}Not my best work, as far as clarity and deep nesting goes. After staring at it for a while, I couldn’t really figure out what was wrong with it. So I built a small test program to debug into, and only then did I see what was wrong.

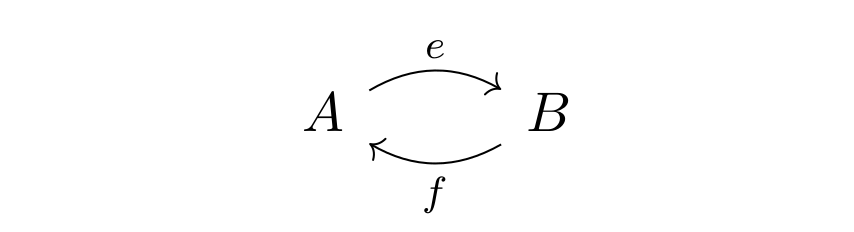

It was terminating the loop after half the file, which now seems pretty obvious given the outcome. But why? Turns out it wasn’t the convert_to_mono at all, but the whole loop. What’s really the problem here is mismatched and imprecise terminology.

What is a sample? The audio signal is usually sampled several thousand times (44.1kHz, 48kHz or 96kHz are common) per second to record the audio waves. One data point is called a sample. But that is only enough of a definition if the sound has a single channel. But all those with convert_to_mono==true were stereo, and that’s exactly were the confusion is in this code. One part of the code thinks in single-channel samples, i.e. a single sampling time-point has two samples in a stereo file, while the other part things in multi-channel samples, i.e. a single sampling time-point has only one stereo sample, that consists of multiple numbers. Specifically this line:

auto samples_in_block = std::min(BLOCK_SIZE, input.sample_count() - sample_offset);samples_in_block and sample_offset use the former definition, while input.sample_count() uses the latter. The fix was simple: replace input.sample_count() with input.sample_count() * channel_count.

But that meant all my stereo sounds, even the longer music files, were missing the latter half. And this was not a new bug. The code was in there since the very beginning of the git history. I just didn’t hear its effects. For the sound files, many of them have a pretty long fade out in the second half, so I can kind of get why it was not obvious. But the music was pretty surprising. My game music loops, and apparently, it also loops if you cut it in half. I did not notice.

So what did I learn from this? Many of my assumptions while hunting down this bug were wrong:

- My brother’s setup did not have anything to do with it.

- Just because the original source file looked fine, I thought the file I was playing back was good as well.

- The bad audio in OBS did not have anything to do with this, it was just recorded too loud.

- The ogg/vorbis encoding was not badly configured.

- The

convert_to_monoswitch or the special averaging code did not cause the problem. - I thought I would have noticed that almost all my sounds were broken for almost two years. But I did not.

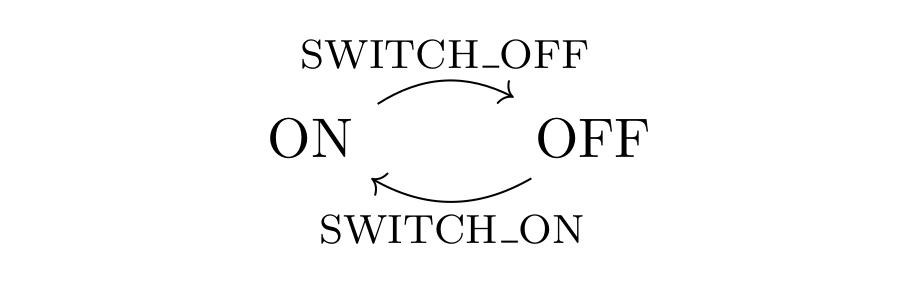

What really cause the problem was an old programming nemesis, famously one of the two hard things in computer science: Naming things. There you have it. Domain language is hard.

- I think this is because this sudden signal drop equates to a ‘burst’ in the frequency domain, but that is just an educated guess. If you know, please do tell. ↩︎